Finding a way out of Lebanon’s crisis: the case for a comprehensive and equitable approach to debt restructuring

prepared by Alia Moubayed and Gerard Zouein

February

2020

The findings,

interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of

the authors. They do not represent the views of their respective employers.

This paper was

finalized based on numbers published at the end of 2019, and before the

outbreak of the Corona Virus. It does not reflect most recent developments and

implications on the Lebanese economy

Synopsis: This paper advocates for an urgent comprehensive growth and fiscal adjustment program supported by the international donor community to deal with Lebanon’s dangerous economic and financial crisis while ensuring an equitable burden sharing of the losses. At the heart of this program, a consolidated balance sheet approach is required for restructuring the country’s debt (both sovereign and Banque du Liban’s) and recapitalizing a right-sized banking sector while protecting small depositors. Using a model-based approach, the scenario analysis argues for taking Lebanon’s debt to GDP to sustainable levels (60-80% of GDP) over the next 10 years. It stresses that the debt restructuring strategy should: 1) encompass BDL’s USD liabilities; 2) design and implement a banks’ recapitalization program that supports a right-sized and solid banking sector able to finance the growth recovery; and 3) ensure the cost of bank recapitalization and the burden of fiscal adjustment are equitably shared through a multipronged socio-economic policy reform framework. The paper estimates that reducing total debt to these levels by 2030 would require no less than a 60-70% principal reduction if the authorities wanted to reduce the extent of an inevitable currency devaluation, and create the fiscal space to support growth and expand social safety nets. Therein, the objective should not be to cut primary spending indiscriminately, but rather to improve its composition and efficiency. The paper warns that inaction and/or delays by using piecemeal solutions is regressive, exacting bigger losses on small depositors and the most vulnerable in society.

Note: The numbers presented in this paper are based on publicly available information as of December 2019 and estimates (e.g. the banking sector USD deposits at BDL, government arrears and contingent liabilities, etc.). As such, the analysis that follows could be subject to material changes should some of this information prove to be substantially different from what is publicly disclosed (e.g. the foreign currency liquidity at BDL). The material is used as part of various citizens’ initiatives which aim to engage stakeholders inside and outside Lebanon in order to shape the priorities and direction of future economic reforms while stressing the importance of an evidence-based policy framework for dealing with the crisis. The authors welcome any comments and suggestions for improvements as the objective of this paper is to help raise awareness about Lebanon’s multifaceted crisis and contribute to the public debate. They also recognize that some aspects of the analysis need further study notably in terms of the legal and regulatory feasibility of some proposals.

Contents

- Introduction

- I- How did we get here? A snapshot of the current situation

- II- Lessons from other “crisis countries”: Where is Lebanon heading?

- III- The need to act: Towards a sustainable recovery and equitable burden sharing

- A- Confirming the net foreign currency position of Lebanon Inc.

- B- Assessing the risk exposure of the banking sector

- C- Reducing the debt stock through a comprehensive and socially just restructuring

- D- Recapitalizing banks while protecting small depositors

- E- Launching a credible and socially responsible medium-term fiscal adjustment program

- F- Mitigating the cost of the adjustment on the most vulnerable

- G- Establishing a credible exchange rate and monetary policy

- H- Boosting private sector growth

- IV- Conclusion

Introduction

Lebanon is in the midst of a dangerous multifaceted crisis: an economic, financial, and socio-political one. Excessive fiscal and external imbalances, financed through debt for decades under a fixed exchange rate regime, weakened the balance sheets of the sovereign, banks and the central bank, and led to a sudden stop of capital that precipitated a debt, banking and currency crisis.

This paper recognizes that the root causes of Lebanon’s unfolding crisis lie in its political system and political economy, and that any exit strategy would require first and foremost a genuine political will to reform. With this in mind, the objective is to analyse the key drivers leading to this crisis, and, building on experiences from other “crisis countries”, highlight possible scenarios for achieving an orderly restructuring. Section 1 provides a quick snapshot of the current situation and how we got here. Section 2 highlights what happened in other “crises countries" drawing conclusions for a more complicated situation in Lebanon. Section 3 outlines scenarios of debt restructuring and balance sheet repair and argues for a comprehensive reform plan to anchor the restructuring process and ensure an equitable burden sharing of the losses. Section 4 concludes.

I- How did we get here? A snapshot of the current situation

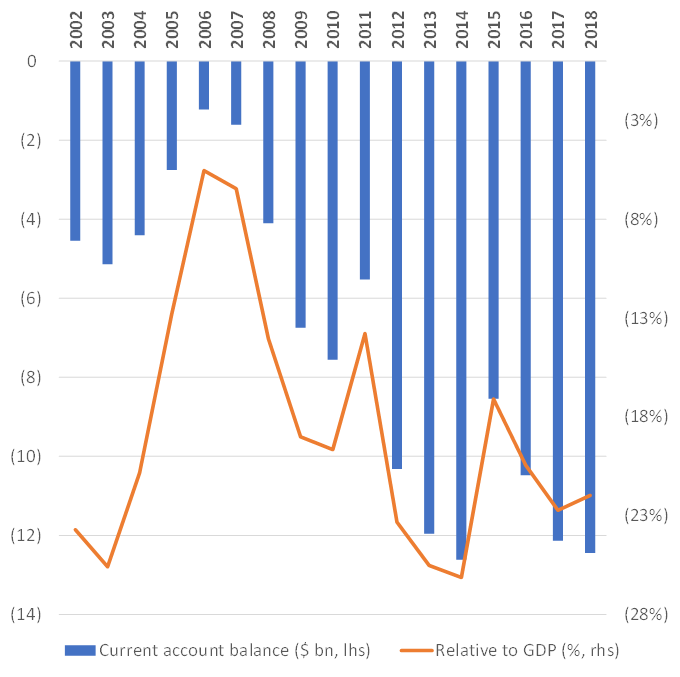

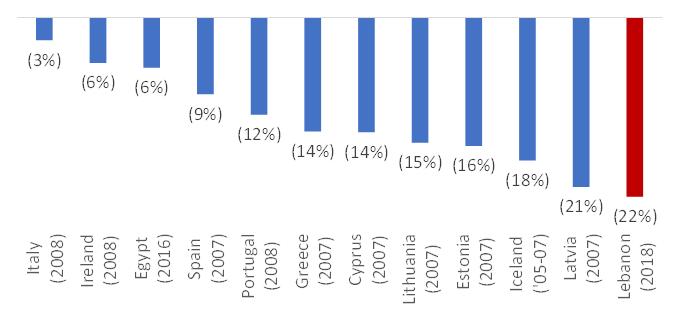

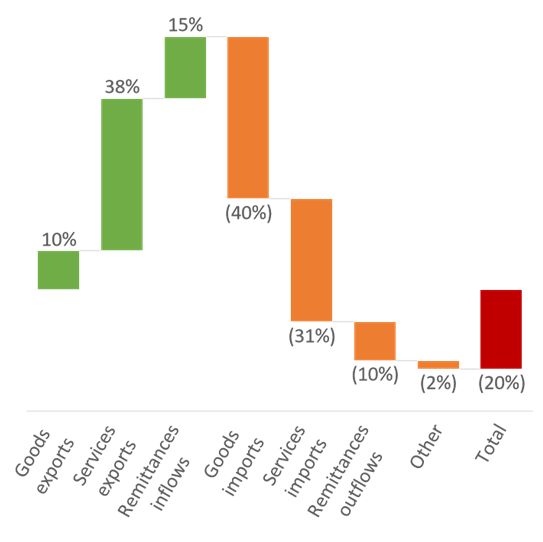

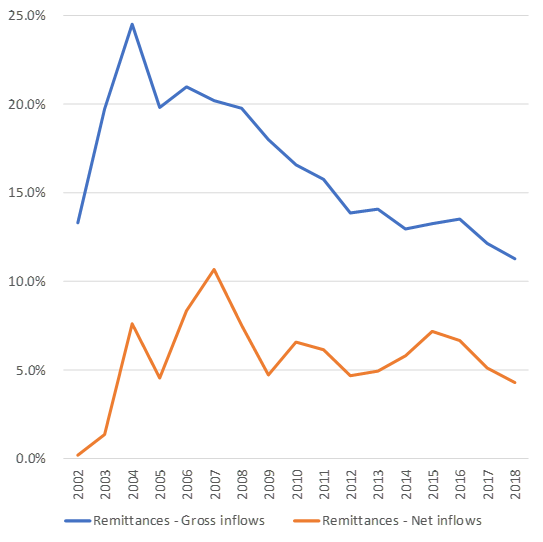

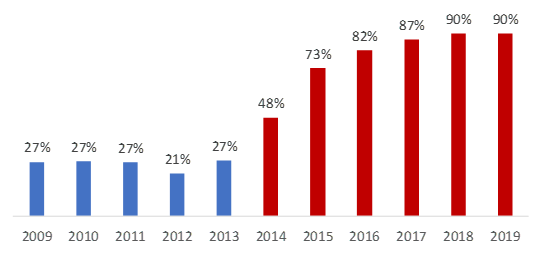

Lebanon has been living above its means for decades. Since 1992, the country has been running large current account (CA) deficits (averaging 18% of GDP per annum from 2002-2018) which widened significantly following the start of the Syrian uprising in 2011 (Figure 1). Compared to other countries that faced similar types of problems, Lebanon stands out as having one of the worst CA deficits at the start of the crisis (Figure 3). Throughout the period 2002-2018, the cumulative CA deficit reached 20% of cumulative GDP: current receipts from goods and services exports and remittances inflows from Lebanese expatriates were outweighed by imports of goods and services, and constant outflows of remittances from foreign workers (Figure 4). The sharp drop in the oil price in 2015 squeezed net remittances further exacerbating the imbalances, as the majority of Lebanese expatriates reside in the Gulf Cooperation Council Countries (GCC) and African commodity exporters, subject to oil and commodity price risks (Figure 5). The decision of maintaining the peg since 1997, even when competitiveness was being eroded, contributed to persistent large external imbalances.

Source: IMF, World Bank, Lebanon’s Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis. Note: *Countries of similar GDP per capita and population >5m. Cumulative since 2002. ** Based on the current account deficit at the start of the crisis (i.e. 2018 for Lebanon) as opposed to Figure 2 which shows the cumulative current account deficit since 2002.

Source: IMF, World Bank, Lebanon’s Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis.

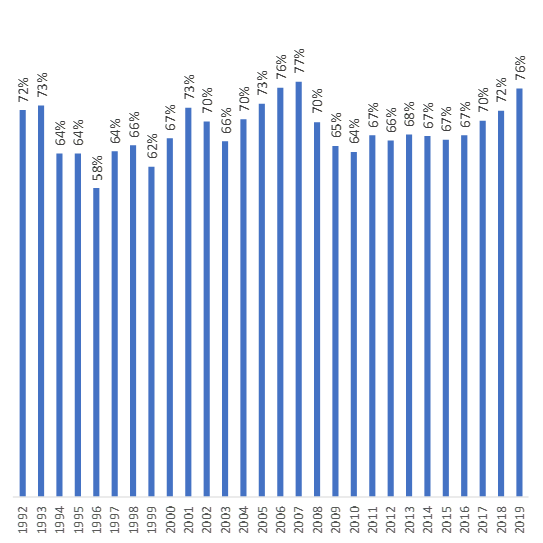

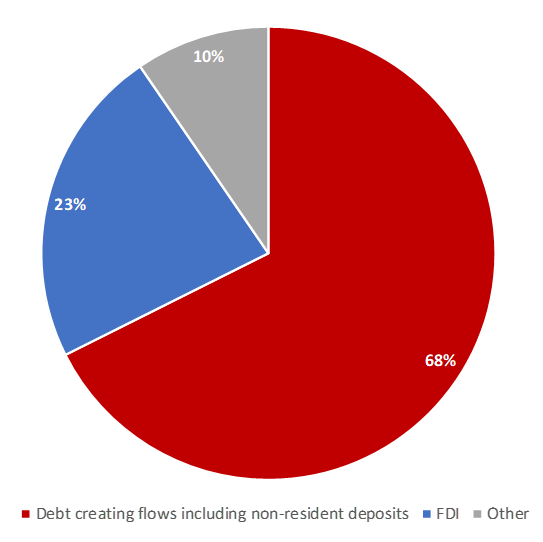

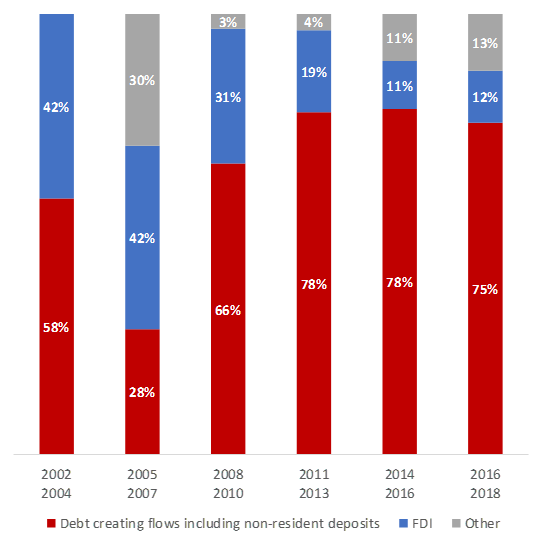

Large external deficits were mainly financed by debt creating flows. Since the early nineties, Lebanon relied extensively on external borrowing and on attracting Non-Residents[1] (NR) deposit inflows (including deposits of the Lebanese diaspora) to fund its large CA deficits. These debt-creating flows covered 68% of the cumulative CA deficits during the period 2002-18 (Figure 6) and saw their share increase overtime at the expense of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) flows. The latter’s share declined rapidly since 2007 largely reflecting unfavourable macro-economic conditions and a deteriorating business environment (Figure 7). Higher interest rates paid to attract the NR deposit base, inflated the net income transfers abroad, compounding a widening CA deficit. Most of these flows did not help fund infrastructure or income generating development projects, but rather went to finance high levels of state capture as well as rentier type of private sector activities (Figure 23).

Source: IMF, World Bank, Lebanon’s Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis.

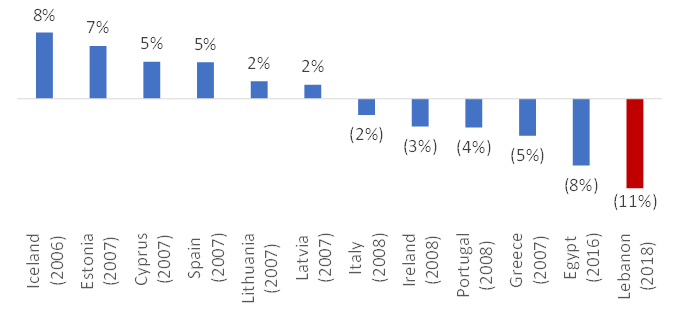

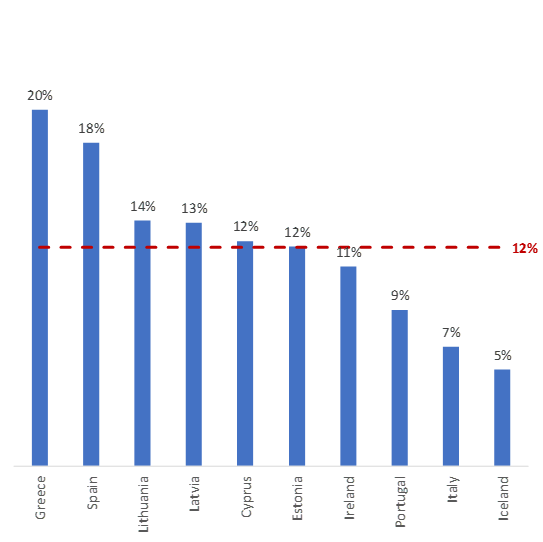

Loose fiscal discipline, increased budget rigidity and an eroding revenue base exacerbated fiscal imbalances. Lebanon’s headline fiscal deficits averaged 9.5% of GDP since 2002. Limited progress on fiscal reforms over the past 15 years resulted in a rigid spending structure with more than 30% of total expenditures absorbed by interest payments and more than 30% by personnel costs including wages, pensions and benefits (Figure 8 and 9). Weak fiscal institutions, and absence of any debt management strategy exacerbated deficits and indebtedness. A badly designed public sector wage increase which was more expensive than originally anticipated, brought wages to 12-13% of GDP, while interest payments accounted for about 10% of GDP. Tax revenues remain low (15% of GDP) compared to 19% of GDP in emerging markets. Lebanon’s fiscal deficit at more than 11% of GDP in 2019, is wider than other countries at the onset of their crisis (Figure 10) such as Greece or Egypt, implying a much more difficult path of fiscal adjustment ahead.

Source: IMF, World Bank, Lebanon’s Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis.

That is not to say that the solution is in cutting spending indiscriminately. While personnel costs to GDP (wages and salaries and social contributions) is amongst the highest in emerging markets and points to the need of public sector restructuring, Lebanon’s primary expenditures (i.e. total expenditures excluding interest, 21% of GDP in 2018) is not out of line with other Emerging Markets countries (EM average 26% of GDP). If at all, Lebanon is one of the highest spenders on education and health in the world, yet with poor outcomes as measured by key human development indicators (PISA scores, HDI, etc.) underscores the need to improve spending composition and efficiency and not only focus on indiscriminate austerity measures, notably by enacting reform of public procurement.

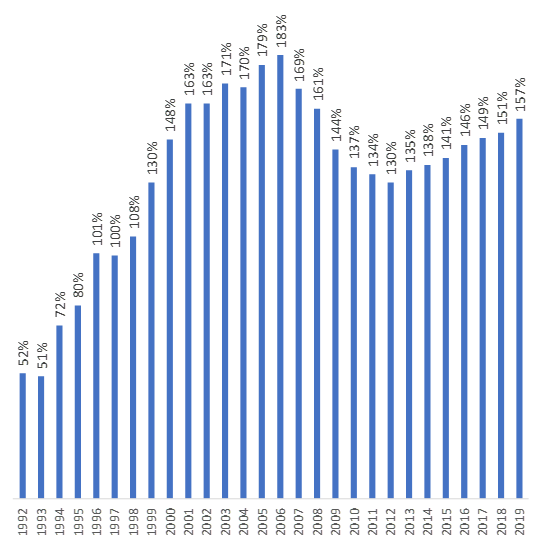

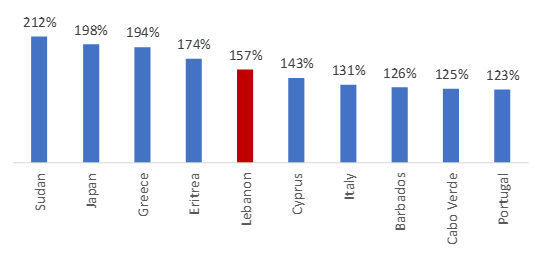

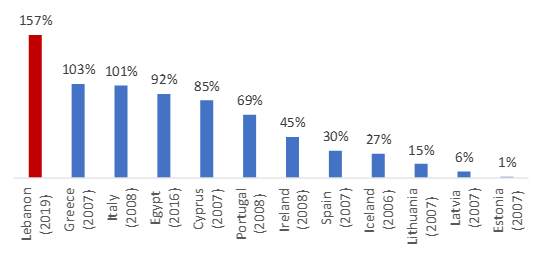

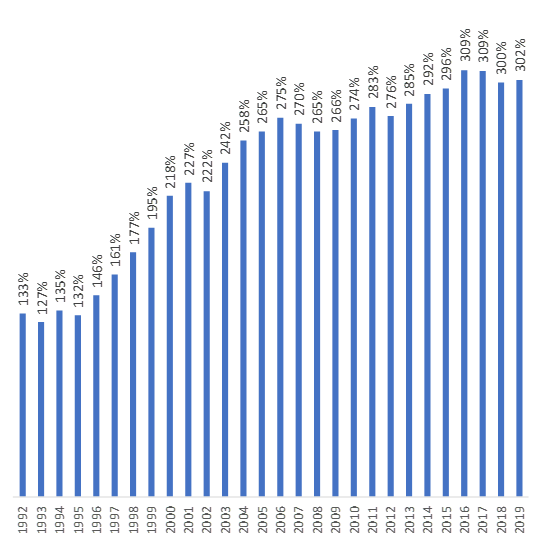

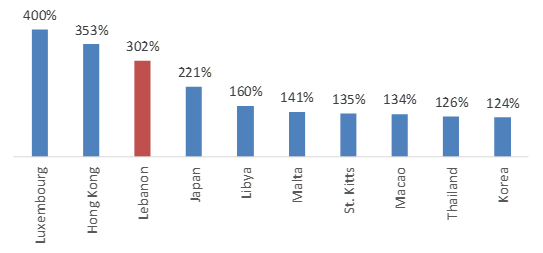

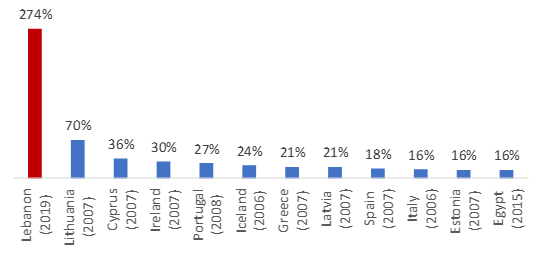

Those unsustainable twin deficits led to a rapid build-up of public and external debt. Debt to GDP rose from a mere 52% of GDP in 1992 to nearly 175% of GDP by the end of 2019 (Figure 11) – one of the highest in the world (Figure 12). It is higher than the debt level of Greece at the onset of its financial troubles (103% of GDP in 2007; Figure 13) ushering that the unfolding adjustment in Lebanon is likely to be more difficult than in Greece. In parallel, external debt (i.e. foreign currency denominated debt) reached 191 % of GDP by the end of 2018 largely driven by rampant foreign liabilities of the banking system, including increases in non-resident deposits.

Source: IMF, World Bank, Lebanon’s Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis. Note: *Countries of similar GDP per capita and population >5m. Cumulative since 2002.

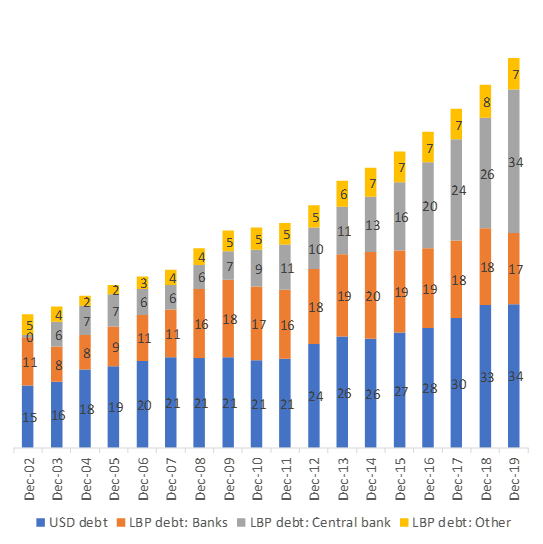

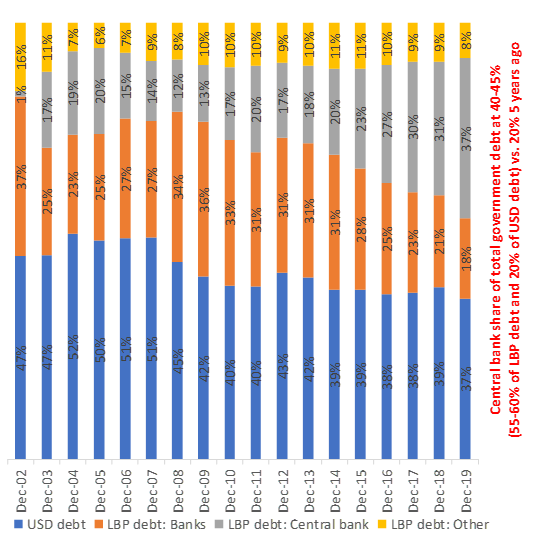

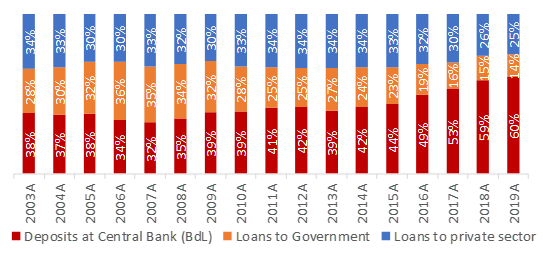

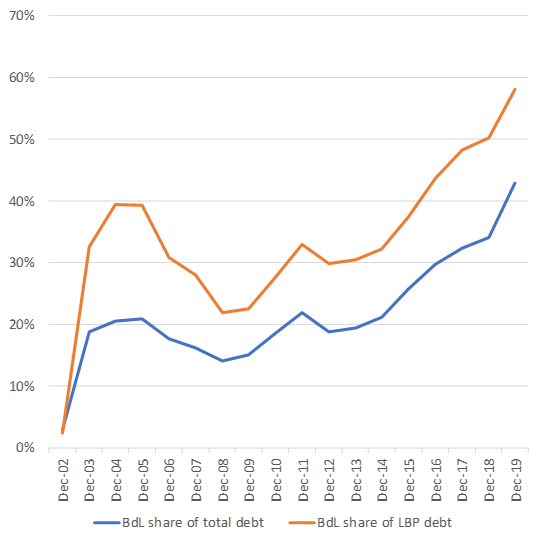

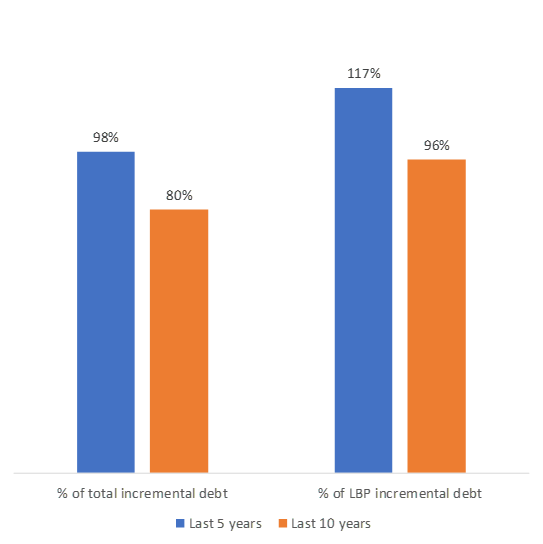

As creditworthiness deteriorated, local banks reduced their exposure to the sovereign, while BDL monetized large and persistent fiscal deficits and debt. External shocks compounded by weak governance, lack of reforms and costly financial engineering operations led to a rapid deterioration in the sovereign and banking sectors’ balance sheets, precipitating an erosion of confidence and a sudden stop of capital. As Lebanon’s access to capital markets became impossible, the share of LBP denominated debt expanded, and notably the share held by BDL: almost 98% of the incremental government debt came directly from the BDL during the last 5 years (Figure 17). Its share in total debt thus reached more than 40% at end of 2019, up from around 20% at the end of 2014; while BDL’s share in total LBP debt rose from 32% to 58% respectively during the same period (Figure 16).

Source: IMF, World Bank, Lebanon’s Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis.

Source: IMF, World Bank, Lebanon’s Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis.

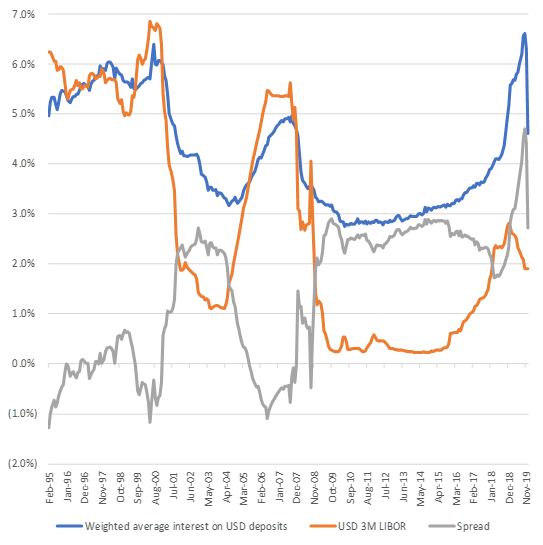

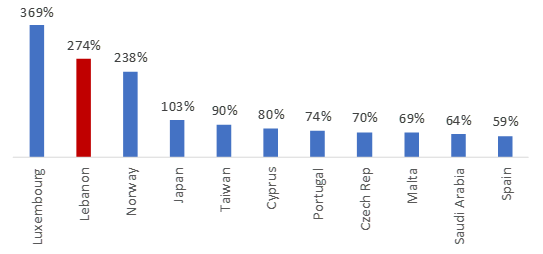

The banking sector’s funding model relied on high interest rates to attract deposits, expanding the deposit base, increasing leverage and stifling growth. The rapid build-up of a large deposit base reached a peak of 309% of GDP in 2016 (Figures 18 and 19). It was largely motivated by attractive spreads on $ deposits (onshore vs offshore) (Figure 21). These spreads rose sharply since mid-2016 (exceeding 4.5%) as the liquidity crunch exacerbated given the dwindling inflows, and as BDL’s financial engineering operations expanded. The latter aimed at bringing fresh $deposits into the banking sector, channelling them into deposits at BDL by offering higher marginal interest rates which gradually led to disintermediation and increased financial repression. This translated into higher LBP lending rates, that stifled growth and pushed Non-Performing Loans (NPLs) higher.

Source: IMF, World Bank, Lebanon’s Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis. Note: * Does not reflect assets held under custody by banking sector hence for example Switzerland does not appear in the chart. Lebanon data is based on December 2019 estimates.

Source: IMF, World Bank, Lebanon’s Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis.

Source: IMF, World Bank, Lebanon’s Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis.

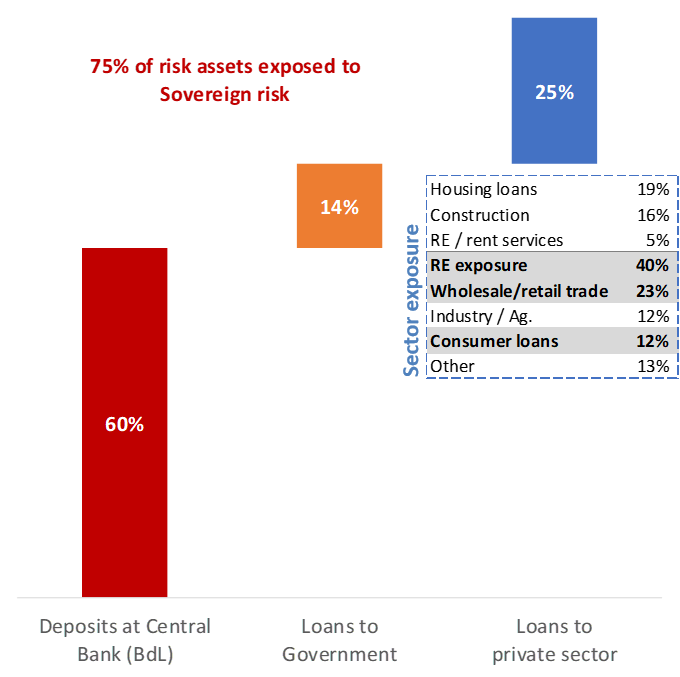

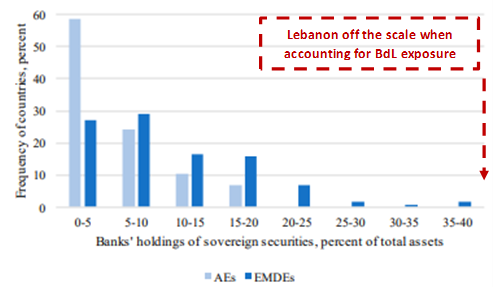

The banks’ increased exposure to BDL inflated the latter’s balance sheet significantly since 2016. The financial engineering operations raised the banks’ exposure to BDL considerably and expanded its balance sheet (Figure 26). At the end of December 2019, about 60% of banks’ risk assets were placed at BDL compared to 38% in 2003 and 44% at end 2015 (Figure 24). The operations provided high marginal returns in LBP and in USD on new bank USD deposits at BDL[2], and boosted BDL’s dollar holdings. The interest earned from banks’ deposits at BDL is estimated to have reached $8 bn to $10 bn in 2018, and inflated paper profits of banks in an otherwise depressed economy. The combined exposure to BDL and government reached thus 75% of total asset, much higher than in other countries (Figure 25). The large deposit base allowed banks to channel up to 25% of the assets (circa $50bn or approximately 96% of GDP) to private sector credits, the majority of which were granted to projects in real estate (40%), trade financing (23%) and consumer loans (12%) (Figure 23).

Source: IMF, World Bank, Lebanon’s Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis.

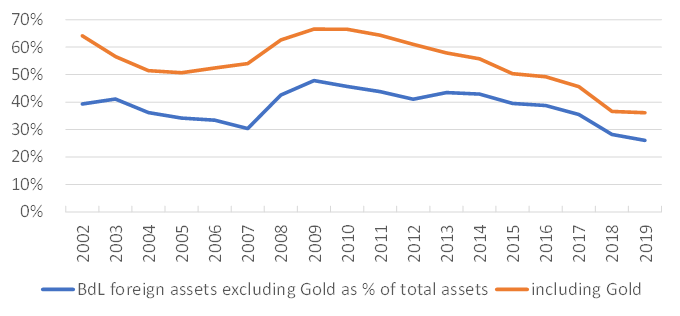

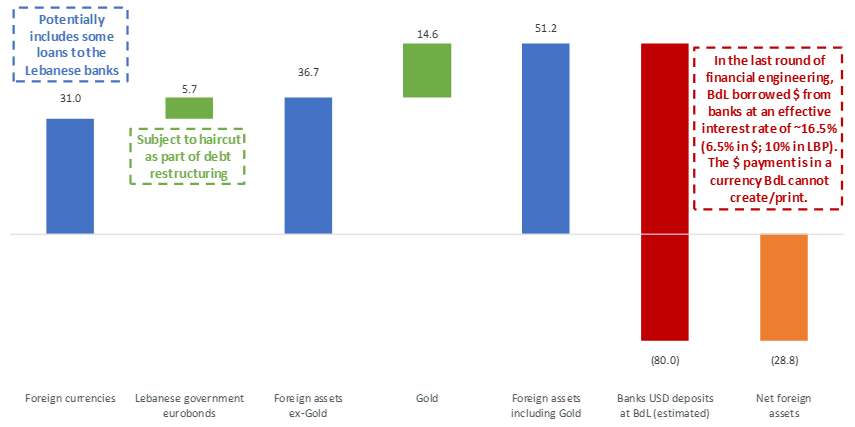

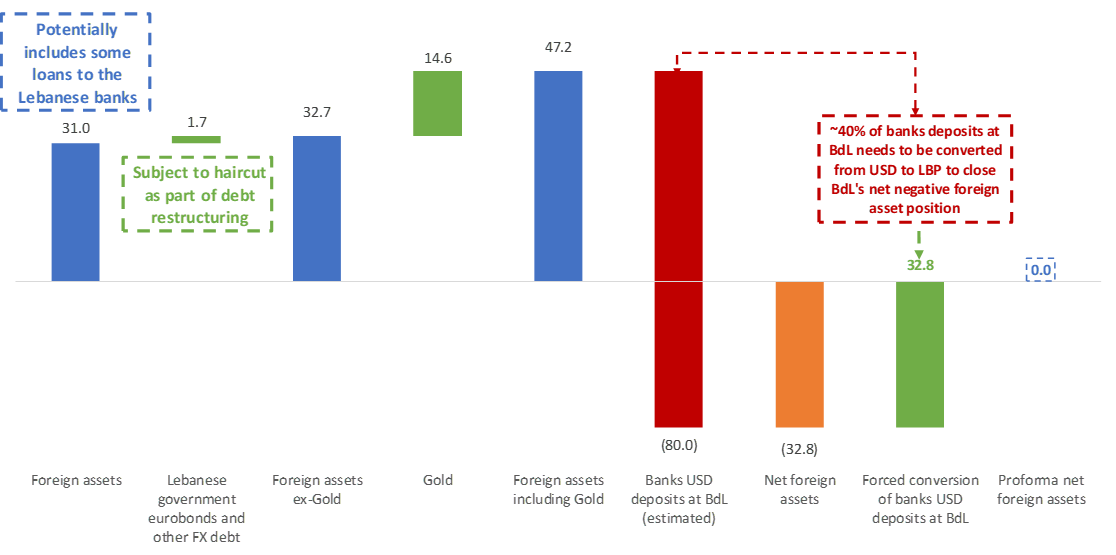

Accordingly, BDL’s net FX position continued to deteriorate and has become one major source of vulnerability, endangering the stability of the banking and monetary system. The increasing use of costly financial engineering operations to fund unsustainable twin deficits over the past few years exacerbated the losses, particularly since 2016, and left a lasting damage on BDL’s balance sheet. Part of the banks’ USD deposits were used to fund the government deficit directly (e.g. through the purchase of Eurobonds and provision of overdraft to the Treasury in USD) or indirectly. Against an estimated $51 bn of foreign currency denominated assets ($37 bn excluding gold), the BDL owes the banks an estimated $80 bn in USD, putting the net negative FX position of the BDL at around $29 bn ($43 bn excluding gold), or approximately 60% of Lebanon’s GDP (Figure 30). The average interest rate that BDL needs to service these USD deposits averages 4-5% (as of September 2019), which amounts to an annual interest accrued of around $3 to $4 bn; and highlights the urgency for dealing with losses. This assumes that the reported foreign currency assets are not encumbered, a claim we cannot ascertain, especially that some local media reports hinted at the fact that BDL’s current available foreign currency liquidity may be less than $31 bn on account of loans from BDL to some banks.

Source: IMF, World Bank, Lebanon’s Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis.

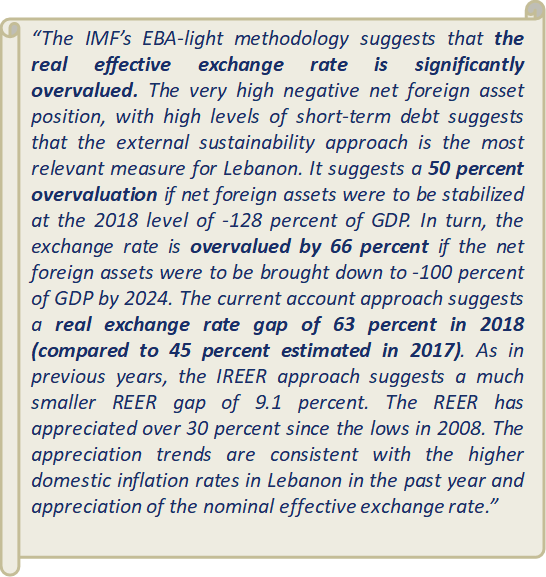

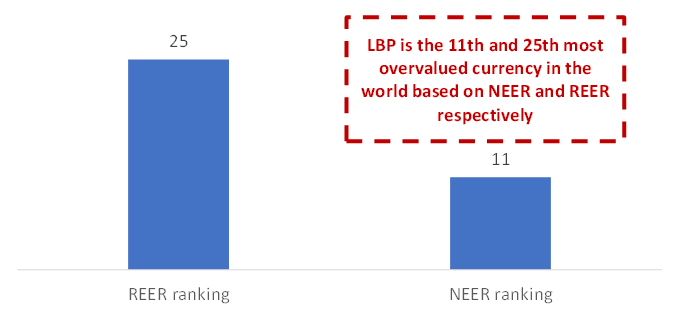

BDL’s deteriorating net negative FX position exacerbated the overvaluation of the Lebanese Pound. Lebanon’s large external imbalances and the large negative net foreign currency position of the BDL (on which BDL is paying high interest rates) suggest a high level of currency overvaluation. The appreciation of the Real Effective Exchange rate (REER) has accelerated since 2015/16 and severely undermined (along with other factors) the competitiveness of the Lebanese economy. In its latest report, the IMF estimated the extent of overvaluation at more than 66% as reflected in increasing REER. While the depreciation of the LBP in the parallel market has caught up with potential fair valuations, there is no comprehensive approach to tackling Lebanon’s macro-structural imbalances, which will continue to exert pressure on the exchange rate.

Source: IMF, World Bank, Lebanon’s Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis. * Based on the IMF Article IV Report; October 2019

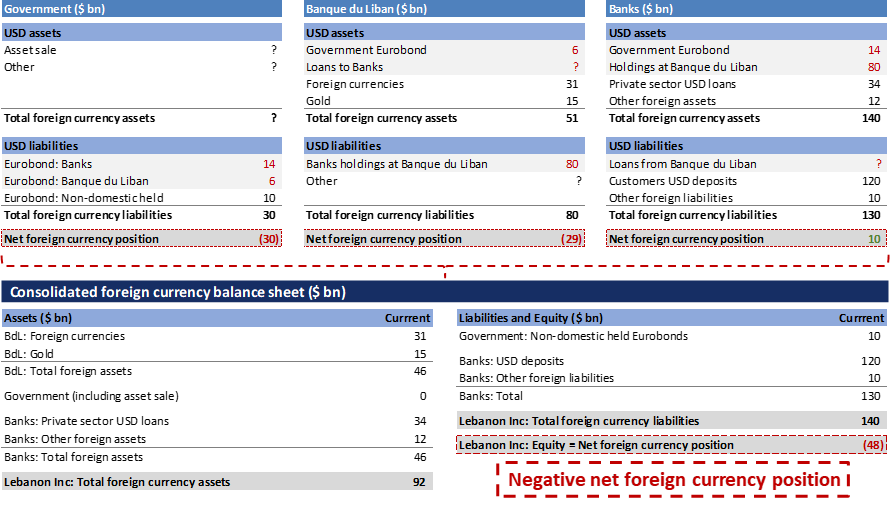

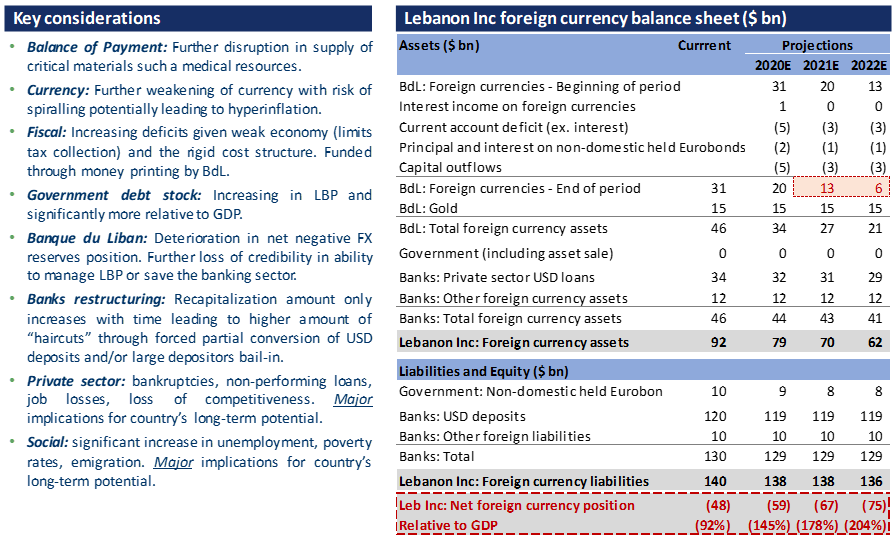

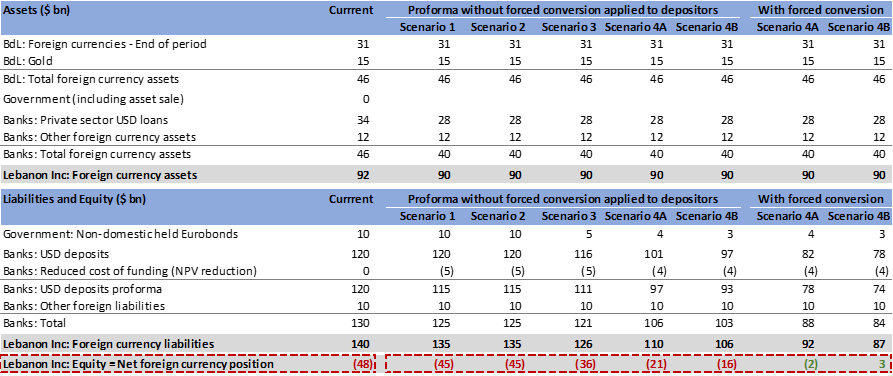

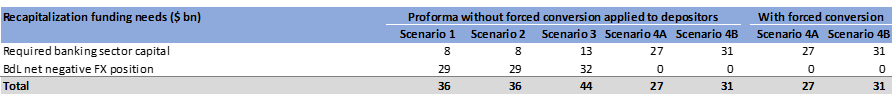

Given the above, we estimate that Lebanon Inc’s net foreign currency position is negative around $48bn, equivalent to ~90% of GDP. We define Lebanon Inc as the merged / consolidated entity that encompasses the main three actors in the Lebanese economy (i.e. the Lebanese Government, BDL and the Lebanese banking sector). As explained above, the entanglement among the balance sheets of the sovereign, BDL and that of banks has increased overtime both in terms of size and complexity. This was largely due to the financial engineering operations that began since 2015/16. We tried to disentangle these debtor/creditor relationships in order to understand the net foreign currency position of each of the entities both on a stand-alone and consolidated basis. Figure 34 highlights that both the sovereign and BDL have net negative foreign currency positions of $30 bn and $32 bn respectively (this excludes the value of state assets in foreign currency such as telecoms and MEA). On the other hand, the banks’ foreign currency assets still exceed their foreign currency liabilities (excluding any potential loans from BDL to the banks which could range between $7 and $13 bn). Accordingly, consolidated Lebanon Inc has a net negative foreign currency position of $48 bn (~90% of current GDP).

Source: IMF, World Bank, Lebanon’s Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis. *Reported BDL’s foreign currency ($31 bn as of 31-Jan-2020) exclude any potential loans from BDL to the banks which could range between $7 and $13 bn. Banking sector data is as of Dec-2019.

This position will deteriorate with time without immediate action to address the crisis. In the face of a sudden stop of capital and given Lebanon’s large external financing needs, pressure on BDL’s gross foreign currency reserves will persist. In our estimate, annual external financing needs in 2020-22 averages around $7bn per year despite a major contraction in the country’s CA deficit (from $26% of GDP in 2018 to around 15-16% in 2020 we estimate). Assuming payment of FX denominated debt maturities are made, this along with the CA deficit in 2020 could take BDL’s gross foreign currency from $31bn[3] at end 2019 closer to $20 bn by year-end and widen Lebanon Inc’s negative position to at least $55 bn or more than 120% of GDP (Figure 51). Failure to take measures to stop the drain on thin USD liquidity at BDL will deepen the insolvency problem at the level of BDL and banks’ balance sheets and increases the risk of a disorderly currency devaluation with serious social and political ramifications.

II- Lessons from other “crisis countries”: Where is Lebanon heading?

The unfolding crisis is multifaceted encompassing a currency, debt, and banking crisis. Stylized facts and experiences from other “crisis countries” could shed light on what awaits Lebanon in terms of economic deterioration and societal tensions in the coming months and years. Looking at these countries, we can conclude that they faced simultaneously the following (among others):

- A sharp fall in their level of economic activity in real and nominal terms;

- A large reduction in their government revenues (in-line with the fall of nominal GDP);

- A rapid increase in banks non-performing loans;

- A substantial drop in banks’ deposits;

- A rise in the level of unemployment.

The section below attempts, by depicting comparisons and benchmarking with some “crisis countries”, to derive assumptions for the modelling exercise presented in section 3, while taking into consideration the peculiarity of the socio-political landscape in Lebanon.

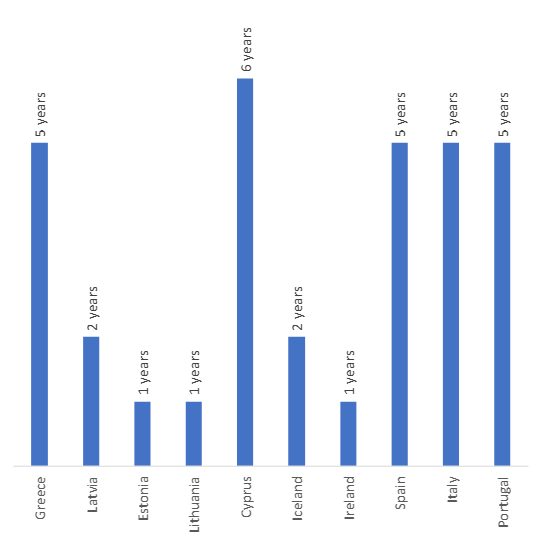

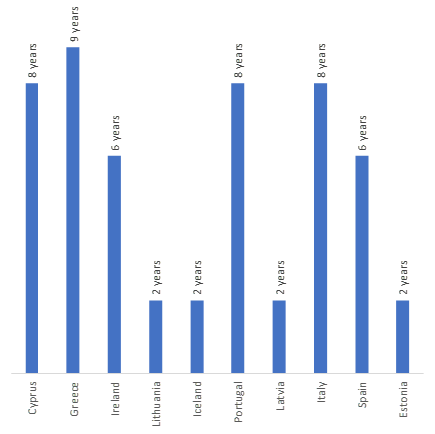

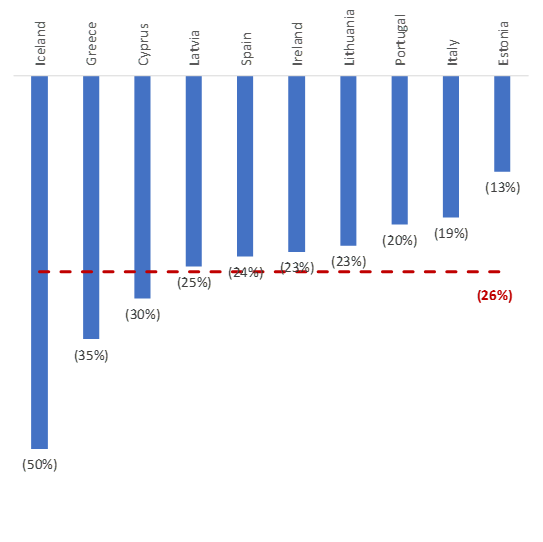

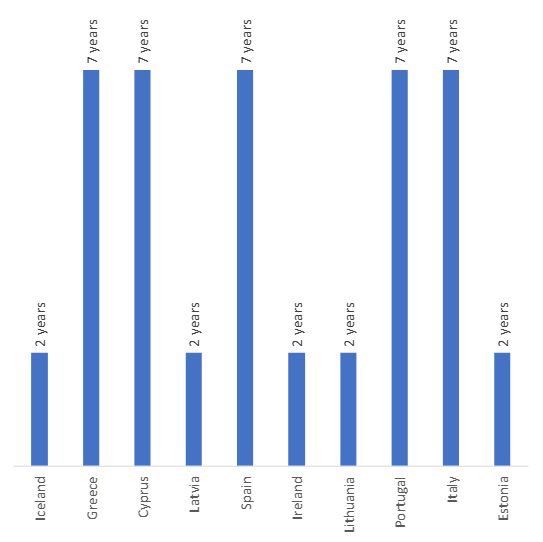

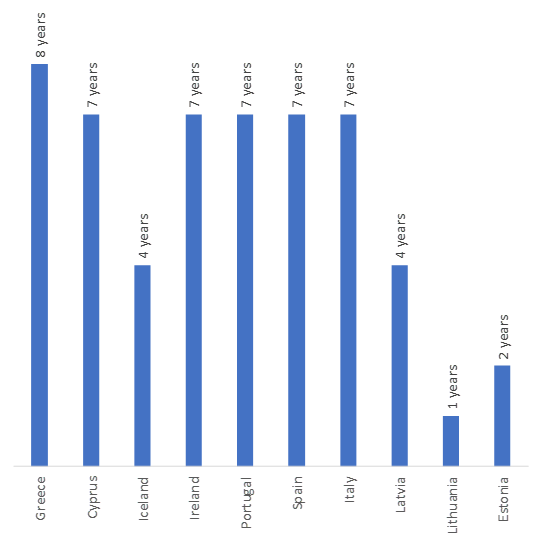

Based on the experience of other “crisis countries”, a severe cumulative contraction in Lebanon’s real GDP is inevitable, most likely to the tune of 20-25% over the next five years. Among the “crisis countries” analysed below, we note that the four largest cumulative contractions in real GDP took place in Greece and the Baltic countries (Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania) (Figure 35). As shown in Figure 13, Greece had the largest stock of government debt relative to GDP at the beginning of its crisis. In addition, Figure 3 highlights that the Baltic countries experienced some of the widest current account deficits that led to a severe external adjustment. Lebanon, hit by a sudden stop of capital inflow, a still large CA deficit and huge debt overhang, is likely to witness a cumulative real GDP contraction of similar magnitude as capital inflows fall sharply and quickly dry up. Recent indicators highlight a major contraction in imports, almost 200 thousand job losses and many companies paying half salaries as discussed below.

Source: IMF, World Bank, national authorities, authors’ analysis.

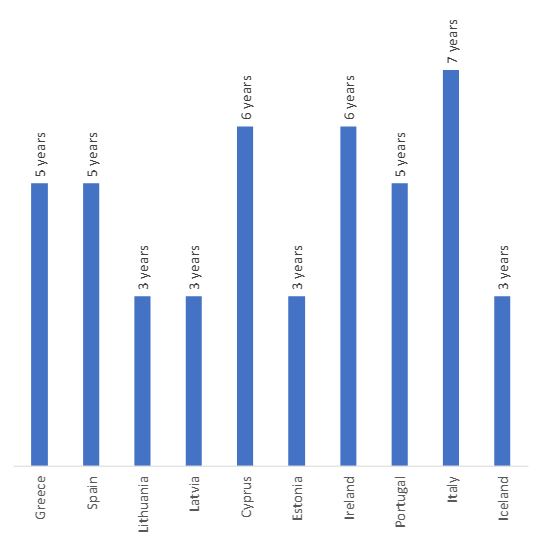

The recovery speed in these “crisis countries” typically depends on policymakers’ actions, and notably the credibility of structural reforms and the depth of debt restructuring. While the recovery in the Baltic countries was fast (Figure 36), it was driven by i) the low stock of government debt at the start of the crisis (~0-15% of GDP) which allowed the government to intervene and expand its balance sheet to support the economy; and ii) the strong foreign ownership of local banks (foreign banks held a market share in excess of 65%) which supported their local subsidiaries, allowing the financial sector to remain stable. Unfortunately, Lebanon cannot currently benefit from similar drivers which could lead to a prolonged period of distress before the recovery happens. A nominal contraction of GDP will also ensue as presented in Figures 37, pushing government debt to GDP up even further.

Source: IMF, World Bank, national authorities, authors’ analysis. *Note: analysis in $ terms i.e. reflects the impact of the currency move on nominal GDP.

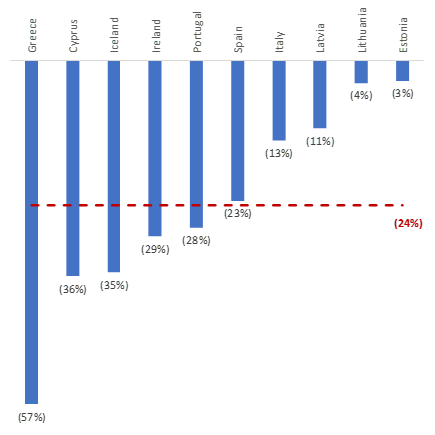

Government revenues will thus drop sharply, exacerbating fiscal imbalances. Experience in other crisis countries suggests a contraction of 25-35%. The large cumulative contraction in real and nominal GDPwill lead to a severe cumulative fall in government revenues as witnessed in all countries that underwent a financial crisis (Figure 39). However, it is worthy to note that the sharpest fall in government revenues was witnessed in Iceland and Cyprus, two countries which had some of the largest banking sectors relative to GDP at the start of their crisis (Figure 20), and where the sector was a major contributor to economic activity, employment and fiscal revenues. In Lebanon, the financial sector’s share of GDP hovers around 9% while it employs around 50 thousand people and contributes about 12% of total revenues to the Treasury. As such, the deepening of the banking crisis in Lebanon could severely impact its government revenues immediately.

Source: IMF, World Bank, national authorities, authors’ analysis. *Note: analysis in $ terms i.e. reflects the impact of the currency move on revenues.

Unemployment will also soar as witnessed in other “crisis countries”, a potential increase of 10 to 20 percentage points over the next few years. The depth of the economic and financial crisis leading to severe GDP contraction also translated in massive job destruction (Figure 41). While in Greece fiscal austerity drove much of the impact on the real economy; in other countries, the banking crisis had also devastating effects on companies. For example, corporate bankruptcies in Iceland increased by more than 50% in the first year of the banking crisis, partly driven by the high currency mismatch between corporate loans and revenues. In Lebanon, the loss of jobs is already happening and accelerating. According to Infopro, more than 220 thousand jobs have been shed, while thousands more employees are being paid half salaries in the private sector. Lebanon’s unemployment rate, which stood at 11.4% (23.3% for the youth) according to the latest survey of the CAS, could thus rise further, notably among youth. Lebanon however may witness a new large wave of emigration that could dampen the rapid increase in youth unemployment. Besides its socio-political implications, the likely loss of skilled labour and talent will have significant ramification on the long-term potential growth of the country. As such, expanding a properly targeted social safety net over the next few years will be critical to mitigate the impact of the crisis on the most vulnerable. The macro-economic scenarios discussed in section 3 assume for that matter an increase in spending on a social safety net of no less than 1.5 percentage point of GDP.

Source: IMF, World Bank, national authorities, authors’ analysis.

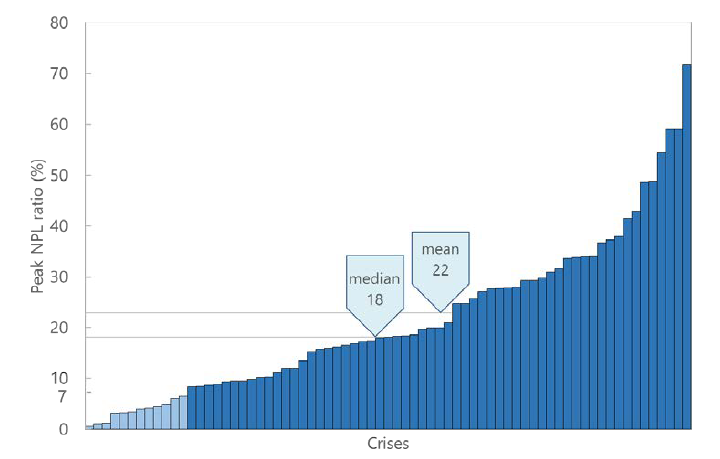

Countries experiencing a banking crisis saw a huge impact on the financial sector’s balance sheet as non-performing loans rose by 20 percentage points (Figure 43). In the case of Lebanon, NPLs stood at around 14% at end September (last available data), but we think this ratio has increased significantly over the past few months. Having said that, the de-facto capital controls imposed and inability to withdraw cash out of the banks has led many to repay loans using existing deposits, which caused the banking sector’s loan books to shrink by around 10% between the end of September and December. Another reason why the increase in NPLs in Lebanon may not be as high is related to the nature of the collaterals with approximately 40% of private sector loans collateralized by real estate and approximately 10% collateralized by cash. The banking sector’s recovery speed depends on the willingness to quickly absorb the losses from non-performing loans and recapitalize the banks, as well as the sovereign’s ability to help. As we discuss below, the ability of the banks to absorb large NPL losses will be limited by the amount of potential losses on sovereign debt and BDL exposure. Moreover, the ability of the sovereign (including BDL) to shoulder a recapitalization is almost non-existent.

Source: IMF, World Bank, national authorities, authors’ analysis.

Experience of banking crisis witnessed in other countries also indicates that deposits would likely shrink by 25-35% over the next few years. The run on deposits witnessed in many of the “crisis countries” typically lasts long, as banking rely on trust and confidence. Should the asset base of the banking sector shrink by a third as suggested below (Figure 45), this will have significant implications on the structure of the Lebanese economy, including employment and government revenues. While official capital controls could be a temporary fix, they need to be transparent, strictly enforceable and accompanied by swift reform measures to address the root cause of the crisis. Unfortunately, the informal and discretionary nature of the capital controls currently in place in Lebanon will only add to the problem by further eroding confidence and intensifying social tensions.

Source: IMF, World Bank, national authorities, authors’ analysis. Note: *in $ terms reflects the impact of the currency on deposits value.

The painful adjustment and economic transformation discussed above happened despite those countries receiving international support and presenting cohesive action plans. All the “crisis countries” analysed above went through painful socio-economic adjustments despite having benefited from the support of the international community (whether under IMF program or through the European Union support mechanisms, or Gulf States funding in the case of Egypt). In most countries, the level of domestic ownership of the reform plans was relatively high; i.e. respective governments presented and adopted relatively solid frameworks and roadmaps which were largely debated within their societies and democratic institutions and put forward by highly competent and professional teams at the level of ministries of finance, economy and the national central banks. In the case of Lebanon, most of these elements are still lacking, and notably a professional and experienced team of policymakers able to engage with both local and international stakeholders in order to manage the crisis and develop the required solutions. Moreover, internal political infighting and geopolitical considerations could complicate the crisis and its resolution process.

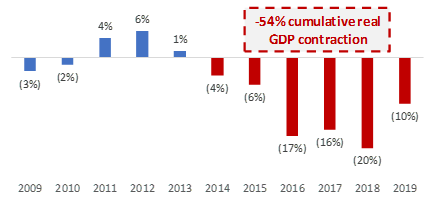

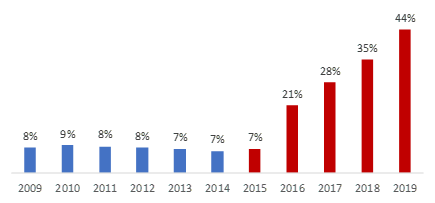

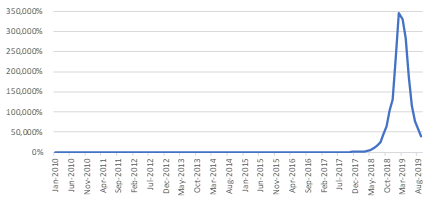

On the other hand, Venezuela presents a live example of a country where the cost of inaction was socially and economically exorbitant. Venezuela has long been dependent on oil revenues. The decline of oil prices, the lax macro-fiscal policies under the Chavez and Maduro governments, US sanctions, a combination of economic mismanagement and corruption at the top and resorting to printing money to fund higher spending, notably social, have contributed to Venezuela’s economic collapse. As shown below, cumulative real GDP contraction reached 54% since 2014 (Figure 47) taking unemployment in 5 years from 7% to 44% by 2019 (Figure 48); while continued monetization of the deficit resulted in hyperinflation (Figure 49), bringing the share of households with income below national poverty line to 90% in 2019, up from 48% at the onset of the crisis (Figure 50).

Source: IMF, World Bank, national authorities, authors’ analysis.

A scenario of no action or delayed reforms in Lebanon, could see reserve depletion by 2022, and lead to a prolonged recession with severe socio-economic consequences. In a scenario of no action, Lebanon Inc’s net negative foreign currency position deteriorates significantly with time. We have outlined below (Figure 51) some of the costs and consequences of inaction including continued monetisation of the deficit, higher inflation and further weakening of growth. The biggest deterioration will take place in BDL’s foreign currencies reserves which could be depleted before the end of 2022 assuming a starting base of $31 bn at end 2019, the persistence of large CA deficit, capital outflows and absence of large external funding. This may be too optimistic, especially if unencumbered USD liquidity at BDL is much lower than reported and that reserves’ depletion will likely be exponential as opposed to linear. In that case, we would expect Lebanon to run out of reserves by end of 2020-early 2021.

Source: IMF, World Bank, Lebanon’s Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis. *BDL data as of 31-Jan-2020. Banking sector data as of Dec-2019.

Based on our estimates, delays in addressing the net foreign currency position of Lebanon Inc will worsen if no policy measures are taken, for two key reasons[4]:

- The current account deficit (excluding interest payments) is estimated to require around $5 bn in 2020 despite it having shrunk significantly, and $3 bn in the subsequent years.

- The Ministry of Finance needs to pay on average over the next 3 years $1.7 bn of interest and $2.2 bn of principal on foreign currency denominated debt (i.e. Eurobonds). It is estimated that approximately one third of these will go to non-resident holders of the Eurobonds implying an average leakage of $1.3 bn per annum from BDL’s foreign currency reserves.

- Capital outflows are estimated to be around $5 bn in 2020 and $3 bn in the subsequent years assuming a proper stringent regulation on capital controls is enacted by June 2020.

Given the sudden stop of capital inflows and the continued depletion of BDL’s gross FX reserves, Lebanon cannot escape a comprehensive liability management, through restructuring much of this foreign currency denominated debt at the level of the sovereign and the BDL. A thorough assessment of the implications on the banks’ balance sheets will thus be necessary as will be discussed in the next section.

III- The need to act: Towards a sustainable recovery and equitable burden sharing

Putting the Lebanese economy on a sustainable recovery path will require a comprehensive approach to address the crisis and exceptional efforts to restore the confidence of the domestic and international communities in the economy and its institutions. This paper is not meant to provide all the detailed elements of a comprehensive program[5], but argues instead that the government and BDL will need to act at two levels and in parallel as soon as possible:

- stop the bleeding through 1) enforcing a transparent and non-discretionary legislation on capital controls; 2) a strategic management of remaining FX liquidity at the BDL; and 3) a mobilization of external (if possible concessional) emergency liquidity to support private sector economic activity and expand social safety nets;

- implement a comprehensive macro-fiscal, growth recovery and social cohesion plan which directly addresses public debt restructuring, rebuilding a positive BDL net FX reserve position and banks recapitalization while protecting small depositors. This should go along with a social rescue plan that expands social safety nets and reforms the pension system. Accelerating governance and institutional reforms is also necessary to improve the business environment, strengthen accountability, and ensure a meritocratic civil service in charge of managing the crisis and public affairs more generally.

The paper advocates a comprehensive consolidated balance sheet approach when dealing with Lebanon’s total stock of debt. It argues that any restructuring of public debt should encompass BDL’s liabilities and accordingly should provide the basis upon which banks’ recapitalization is designed and implemented. By presenting various scenarios using model-based approach, the analysis outlines the assumptions about the path of policy variables necessary to take Lebanon’s debt to GDP to sustainable levels (60-80% of GDP) over the next 10 years through a multipronged policy reform framework discussed below.

We would note that the numbers presented in this section are based on publicly available information and estimates as at December 2019 (e.g. the banking sector USD deposits at BDL, government arrears, distribution of deposits…). As such, the analysis that follows could be subject to material changes should some of this information prove to be substantially different from what is publicly disclosed (e.g. the foreign currency liquidity at BDL).

A- Confirming the net foreign currency position of Lebanon Inc.

At the onset, it is critical to confirm the magnitude of Lebanon Inc’s net negative foreign currency position through a professional and independent audit. The entanglement among the balance sheets of the sovereign, BDL and banks has increased overtime both in terms of size and complexity. Any restructuring solution that only reduces intra Lebanon Inc’s liabilities (i.e. between the Government, BDL and banks) without reducing Lebanon Inc’s consolidated liabilities to third parties would not solve the core problem and could only aggravate and delay the inevitable adjustment. As shown in Figure 34 above, Lebanon Inc’s net foreign currency position is estimated to be negative, bn -48bn or almost ~90% of GDP by end December 2019. It is thus extremely important that the new government establishes a comprehensive independent audit of the sovereign, BDL and banks’ balance sheets and acknowledges their net position in both local and foreign currencies.

B- Assessing the risk exposure of the banking sector

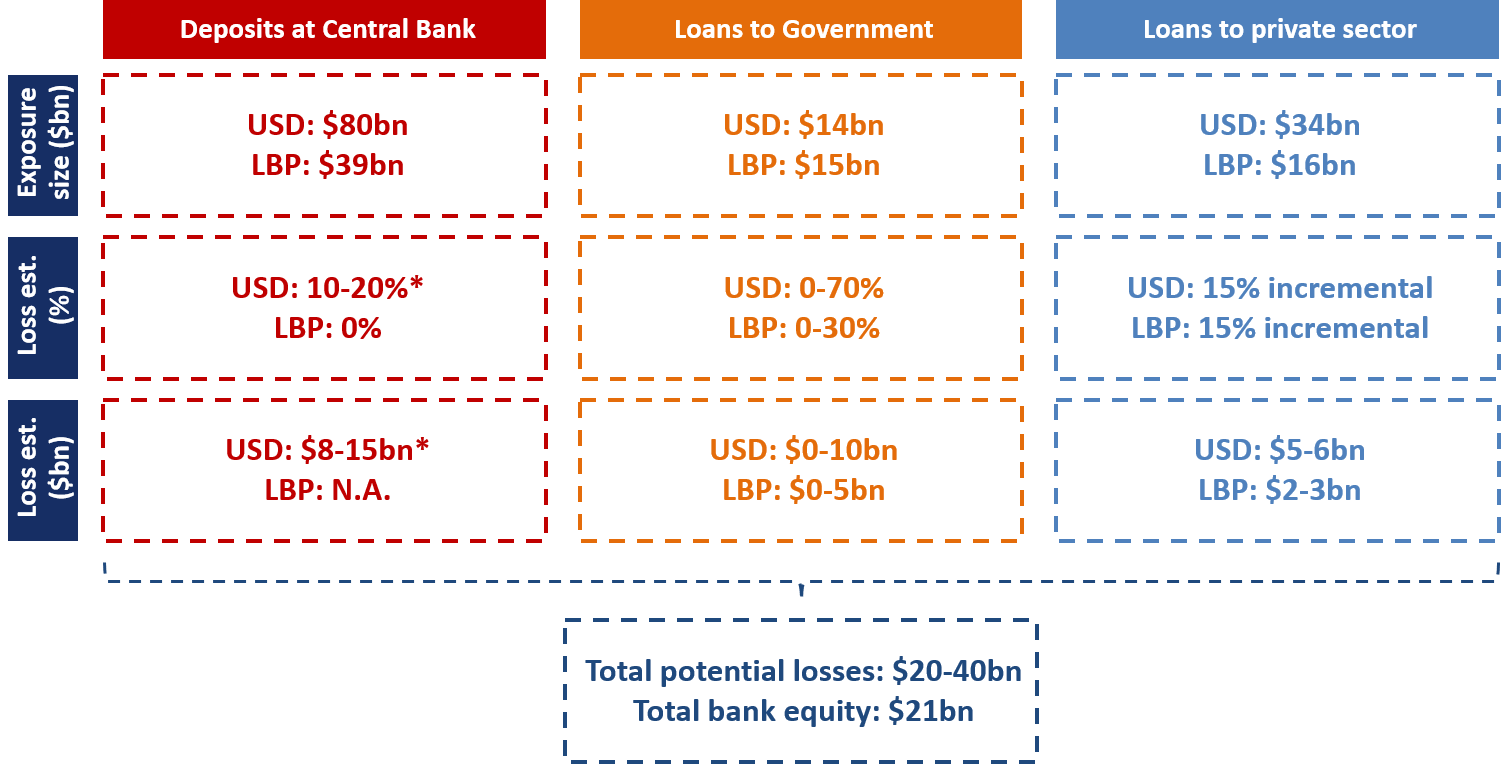

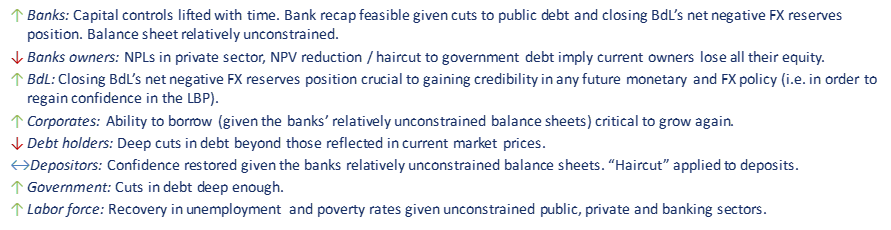

The Lebanese banking sector is exposed to three major credit risks: BDL risk, government risk and private sector risk.As the economy goes deeper into the recession undermining banks’ asset quality, a potential restructuring of sovereign and BDL’s debt held by banks will have a material impact on their balance sheets as explained in Figure 52 below. These multiple concomitant shocks will require a momentous effort to recapitalize a right-sized banking sector and protect depositors, notably the smaller ones.

- Loans to the private sector: The exposure of the Lebanese banks to the private sector as of December 2019 amounts to $50bn (of which $34 bn in USD and $16 bn in LBP). Experience in other “crisis countries” (Figure 43) suggests incremental losses of 20 percentage points on private sector loans over a period of two to nine years depending on the depth of the crisis. Assuming further reductions in loans as borrowers rush to offset loans with trapped deposits, we applied a relatively limited increase of 15% in NPLs (i.e. an increase from 14% at the end of September 2019 to 29% at peak) leading to an incremental loss of $7 to $9bn on the banks’ private sector loan portfolio. This is in line with a recent IMF study on the dynamics of NPLs during 88 banking crises since 1990, which suggests a median peak of NPLs relative to the level at the start of the crisis of 1.8x and an average of 2.9x (Figure 53 and 54). If we assume an increase of 30% in NPLs (instead of 15%), the incremental losses for the banking sector will amount to $14-$16bn[6]. Our analysis doesn’t account for the recent circular issued by BDL waiving IFRS9 implementation, as any recapitalization of the banking sector should be done based on international standards in order to restore confidence in the banks and maximize their ability to attract foreign capital.

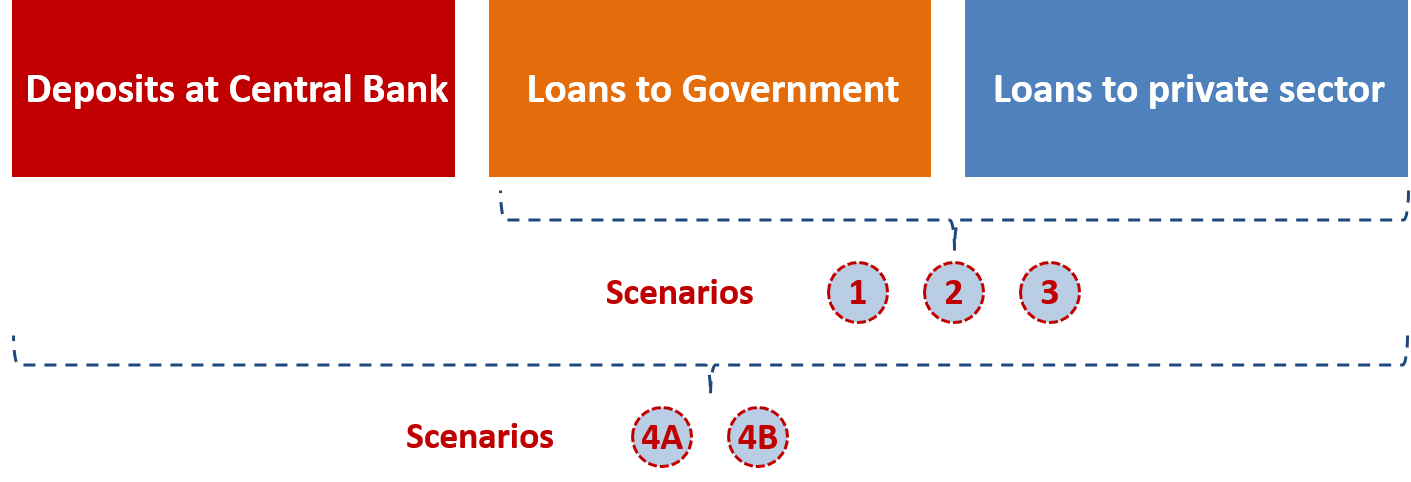

- Government debt: While banks have significantly reduced their government exposure, they still hold about 36% of total sovereign debt, $14 bn in USD (Eurobonds) and the equivalent of $16 bn in LBP (T-Bills/Bonds) (Figure14). As the sovereign creditworthiness deteriorates, and the government’s ability to repay diminishes, the cost of servicing this debt rises further. Lebanese officials have been discussing possibilities for debt re-profiling. Below, we model 5 different scenarios for the restructuring of government’s debt: scenarios 1 to 3 do not deal with BDL’s negative FX position while scenarios 4A and 4B address this large negative gap. The banks losses from government debt restructuring could reach up to $15bn.

- Deposits at the Central Bank: Local banks have increased their exposure to the BDL against lucrative returns as explained above (Figure 23 and 24), helping the BDL shore its gross FX reserves using depositors’ money. At the end of December 2019, banks’ asset at BDL were estimated at around $119 bn or 60% of total. As seen in Figure 30, BDL’s net foreign currency position is estimated to be negative at $28.8 bn (including gold) or approximately 60% of GDP, assuming its available foreign currency assets are unencumbered. The losses to the banks from adjusting BDL’s net negative position could reach up to $33bn depending on the approach adopted as explained below.

Source: IMF, World Bank, Lebanon’s Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis. Note: * Estimated losses based on BdL estimated net foreign FX position of $33bn. ** IMF working paper: “The Dynamics of Non-Performing Loans During Banking Crises: A New Database.” by Anil Ari, Sophia Chen, Lev Ratnovski.

C- Reducing the debt stock through a comprehensive and socially just restructuring

Creating the needed fiscal space to support growth and expand social safety nets will require a reduction in the public debt stock at the onset of the adjustment process. As highlighted in Figure 8, interest payments account for 10% of GDP, or more than a third of total spending. Containing the fiscal deficit and ensuring a sustainable debt profile will thus require a significant reduction in the stock of debt. For that purpose, we model different possible scenarios for debt restructuring. We highlight below some key underlying economic assumptions used in the model.These assumptionsbuild on country experiences analysed in section 2, while adapting it to Lebanon’s specific context based on available data, with the aim of improving revenues and increasing spending efficiency in a way that supports growth and preserves social stability. In particular, the model assumes:

- Real GDP contraction of ~20% to 30% cumulative over the next 5 years (starting in 2019). This is in line with the impact witnessed in other “crisis” economies (Figure 35) and factors in the recessionary effects of capital controls, currency devaluation and liquidity crunch increasingly confirmed by reported bankruptcies and job losses.

- Exchange rate is devalued upon restructuring and settles at 2,600 based on the IMF’s assessment of LBP overvaluation (Figure 31).

On the fiscal front, the policy stance aims at raising revenues and improving the quality and efficiency of public spending to support growth and social cohesion. As such, the model assumes the following:

- Government primary spending is likely to remain constant relative to GDP. Lebanon’s primary expenditures averaged 21.2% over the past ten years, compared to 26.6% in Emerging Markets. The need is therefore not for reducing the level of spending but rather improving its efficiency and composition, notably through the following:

- Transfers to EDL are projected to be reduced gradually as energy reforms move forward and are eliminated in 5 years.

- Real value of public sector wages is partially preserved by 75% increases in nominal wage in 2020 (the year the exchange rate is devalued), effectively cutting public wages by 40% in real terms in parallel with major efforts to restructure state institutions and State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) and reforming the civil service to strengthen accountability[7].

- Social safety nets expansion in the medium-term of ~1.5% of GDP per year over next 5 years.

- Capital expenditures are projected to initially shrink as government revenues collapse. We grow capex again in 3 years (2022) relative to 2019 in both absolute terms and relative to GDP.

- Government revenues are expected to shrink in absolute terms and relative to GDP, and possibly outweigh the contraction in GDP as they depend on the banking sector, trade (customs duty) and consumption (VAT), all of which will sharply drop during a recession. However, fiscal reforms will target raising revenues while strengthening an equitable wealth redistributing tax system. Under scenarios 1 to 3, we project government revenues to improve to 22% of GDP closing half of the gap vs. EM countries tax revenues (% of GDP). Under scenario 4A-4B, we project government revenues to improve to 24% in 10 years closing the gap vs. EM countries tax revenues (% of GDP).

On the external front, we estimate the current account (CA) deficit to shrink from $12bn to around $5- bn in 2020-21 as severe contraction in economic activity, the sudden stop of capital inflow and the banking crisis are already causing a massive adjustment in the trade deficit, while remittance inflows are slowing down and flowing through informal cash channels. Moreover, the restructuring of the debt will likely reduce outflows associated with debt service over the coming 5 years.

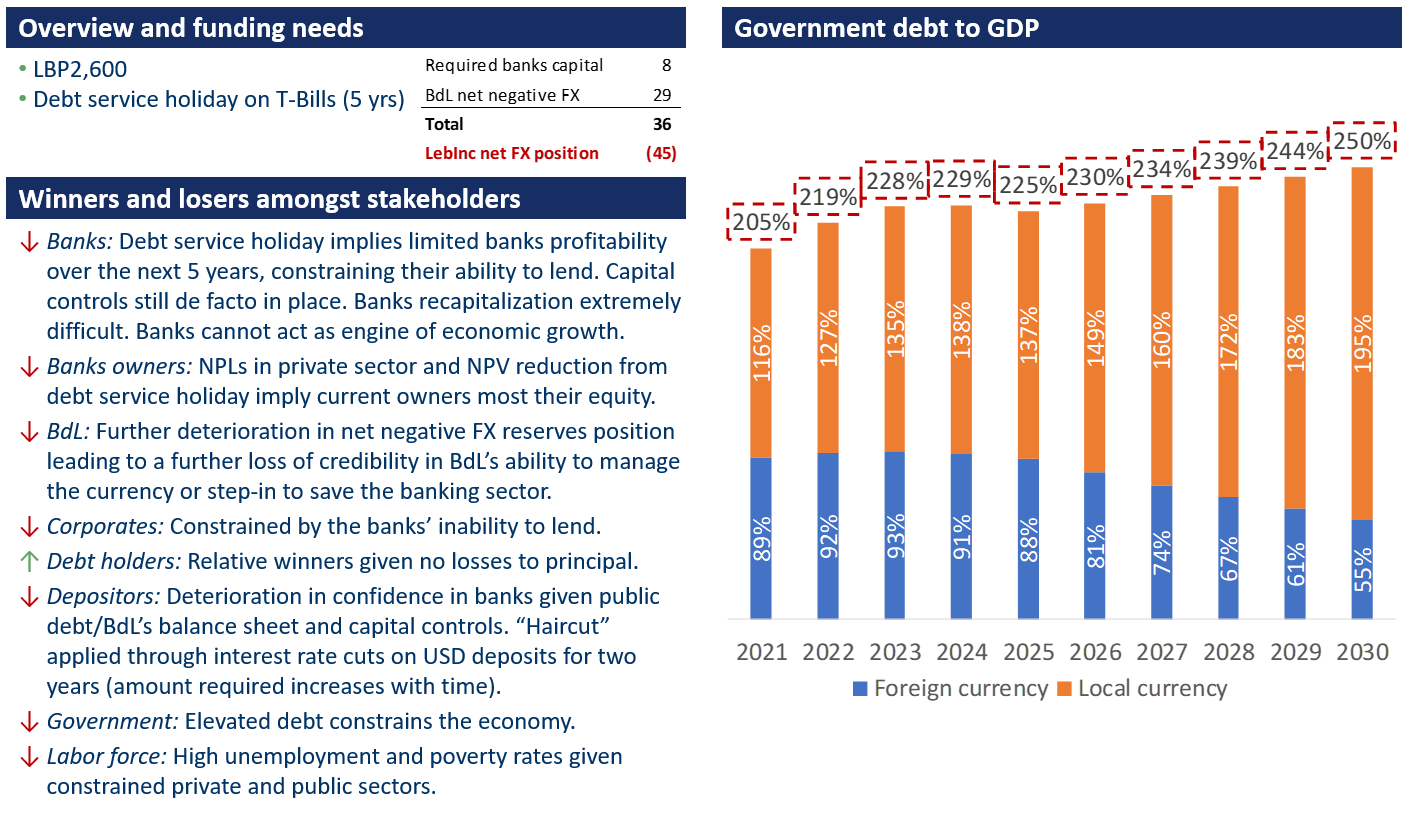

Scenario 1 – Five-year debt service holiday on LBP TBs

A scenario limited to postponing debt service on LBP denominated debt will keep Lebanon worse off for the foreseeable future. First, this approach does not deal with the debt stock problem thus weighing on growth and the fiscal stance. Assuming fiscal consolidation around 1.6% of GDP of primary surplus by 2025, this would leave debt to GDP in 2025 at 225% of GDP, much higher than its current level (Figure 55). Second, Lebanon’s interest payments in foreign currency (averaging $3.5 bn per year over the next 5 years) will worsen BDL’s net negative foreign currency position and keep the public sector, the banking sector and BDL constrained, while capital controls remain in place. Banks will also be under pressure as their balance sheets remain impaired by higher NPLs and no interest on LBP government debt. Under this scenario, we estimate that the impact on banks, and therefore required recapitalization, will hover around $8bn (Figure 55).

Source: IMF, World Bank, Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis. * Required bank capital refers to recapitalization needs for banks to meet a target of 8% RWA. Note: Liability management on LBP denominated debt does not involve Treasury bills/bonds held by the National Social Security Fund.

Scenario 2 – Debt service holiday on LBP TBs for 5 years + Cancellation of BDL’s LBP TBs portfolio

A proposed cancellation of the BDL’s portfolio of LBP denominated government debt, in addition to the debt service holiday for banks, will keep Lebanon in a debt trap for another decade. This scenario attempts to deal with part of the debt stock only, without addressing the ability to service foreign currency liabilities given BDL’s net negative FX position. Assuming fiscal consolidation at a slightly higher pace than in scenario 1, reaching 2.2% of GDP of primary surplus by 2025, this would leave debt to GDP in 2025 at 171% of GDP (Figure 56), above its current level. For the same reasons highlighted in scenario 1, the public sector, the banking sector and BDL will remain constrained and confidence in the system dented. The required banking recapitalization will be as in scenario 1, i.e. around $8 bn. Moreover, the implications for recapitalizing BDL following local debt restructuring are likely to be inflationary and will need to be addressed through other policy measures to limit its impact on the most vulnerable. In Figure 56 below, we show the winners and losers amongst key stakeholders. We have highlighted in red the changes compared to the previous scenario.

Source: IMF, World Bank, Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis. * Required bank capital refers to recapitalization needs for banks to meet a target of 8% RWA. Note: Liability management on LBP denominated debt does not involve Treasury bills/bonds held by the National Social Security Fund.

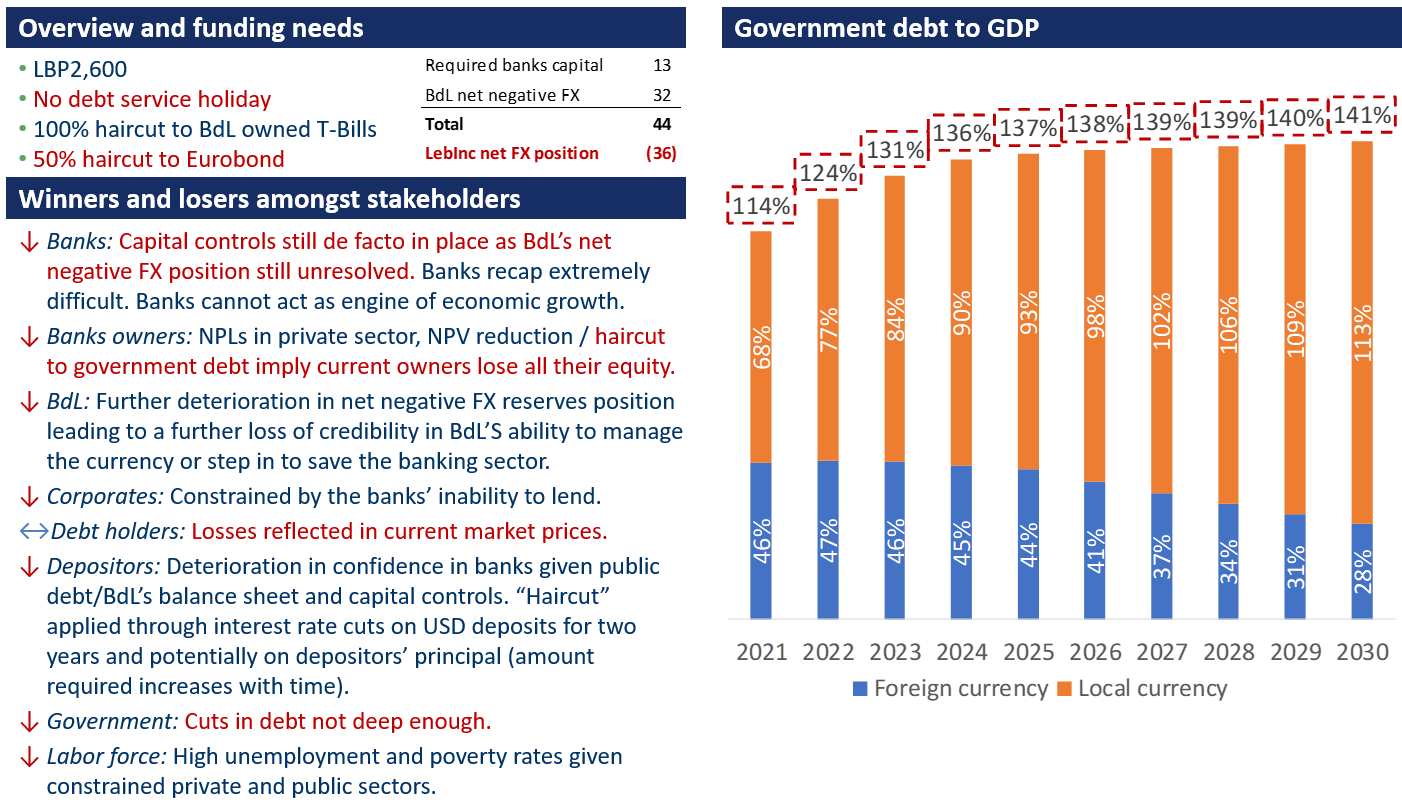

Scenario 3 – BDL’s LBP TBs portfolio + 50% Eurobond haircut

A cancellation of BDL’s LBP debt portfolio and a 50% haircut on the Eurobonds will not be enough to put the debt on a sustainable path. Assuming fiscal consolidation at a slightly higher pace than in scenarios 1 and 2, reaching 2.9% of GDP of primary surplus by 2025, this would leave debt to GDP in 2025 at 137% of GDP (Figure 57). Although the extent of initial debt stock reduction under this scenario is significant (debt to GDP falls to 114% in year 1 post restructuring), BDL’s net negative foreign currency position at $32 bn (post 50% haircut on Eurobonds) will render recapitalization of the banking sector difficult (estimated at $13 bn). Investors will remain reluctant to invest in a sector that is exposed to a central bank with a hugely encumbered balance sheet. Low confidence in the currency and a medium to high risk of prolonged economic contraction will weigh on the country’s fiscal position and its medium-term debt sustainability prospects. We have highlighted in red the changes compared to the previous scenario.

Source: IMF, World Bank, Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis. * Required bank capital refers to recapitalization needs for banks to meet a target of 8% RWA. Note: Liability management on LBP denominated debt does not involve Treasury bills/bonds held by the National Social Security Fund.

As shown in Scenarios 1 to 3 above, Lebanon’s public finances will remain unsustainable if debt restructuring is limited to the stock of government debt, without tackling BDL’s net FX position. The latter will continue to deteriorate as BDL’s foreign currency liabilities will increase while its foreign assets dwindle as shown in Figure 51. In an environment where private sector credit remains weak, and net claims on government are on the rise as the BDL prints money to fund the fiscal deficit, persistent negative net FX position at BDL has severe implications for the economy:

- Capital controls will persist for years to come without an end in sight;

- The exchange rate will remain under pressure as risks of devaluation loom;

- Economic activity will remain subdued while inflationary pressures mount;

- Banks’ exposure to BDL will limit ability to fund and support growth;

- External funding/support to revive the economy will remain limited;

- Loss of confidence due to high risk of recurring crisis.

As such, targeting fiscal and external sustainability without addressing BDL’s net negative foreign currency position as part of the debt restructuring is elusive. However, a comprehensive balance sheet approach along the one suggested under Scenario 4 below may yield results if properly implemented.

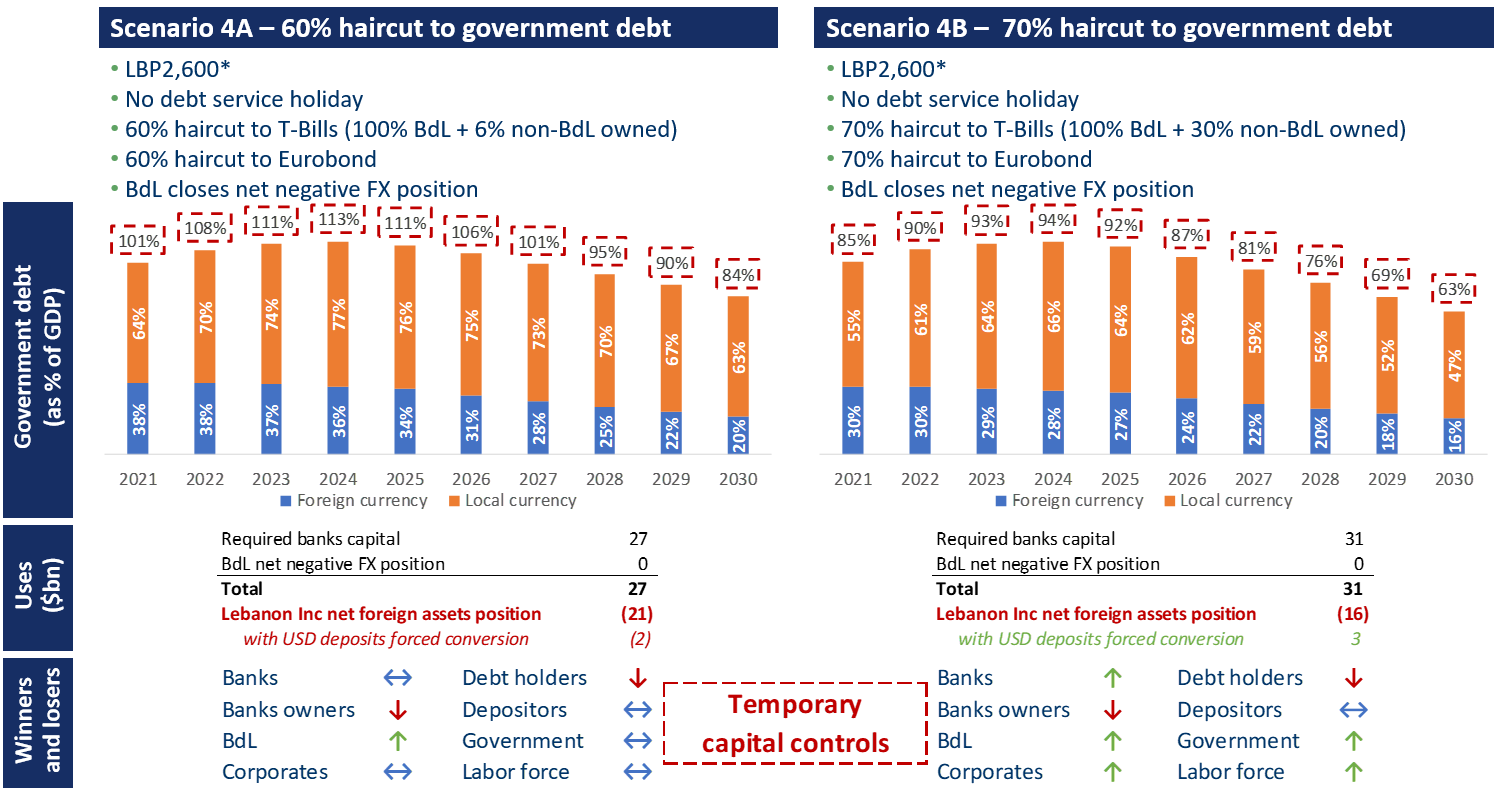

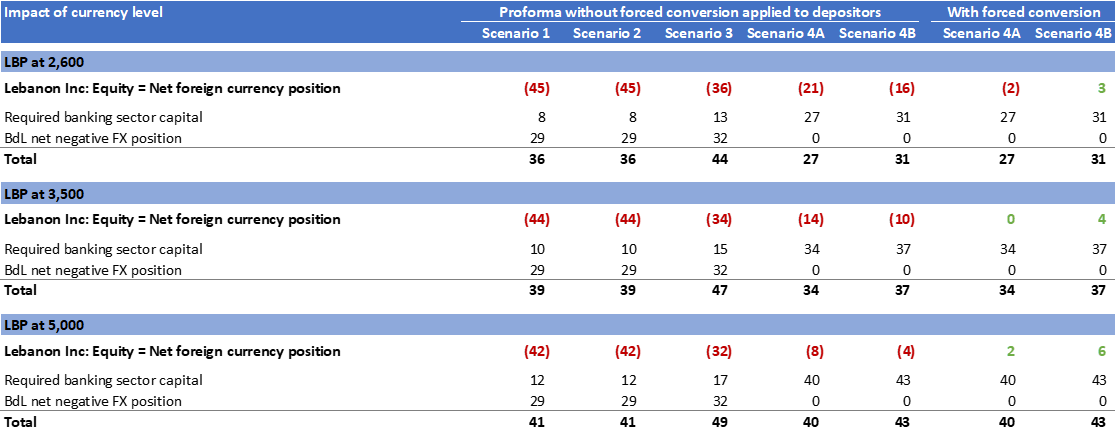

Scenario 4 – Dealing with BDL’s balance sheet + 60-70% haircut on total debt (Eurobonds & TBs)

The objective of this scenario is to bring Lebanon close to an investment grade rating targeting debt to GDP of 60-80% by 2030, and to rebuild BDL’s net foreign currency reserves to adequate levels. Assuming fiscal consolidation at a higher pace than in scenarios 1 to 3 reaching 3.8% of GDP of primary surplus by 2025, and growth to recover at a faster pace than in scenarios 1-3 as a result of the gradual lifting of capital controls and the pursuit of bold structural and fiscal reforms, debt to GDP would be around 84% by 2030 if we limit the haircut to 60%. A haircut of 70% on total debt could bring debt to GDP to 63% by 2030 (Figure 58). This is a dramatic and very deep debt restructuring that will need to be anchored within a comprehensive, credible and internally consistent medium-term fiscal and growth recovery plan. Without doing so and addressing BDL’s net FX position (estimated to be around $33bn post debt restructuring), it would be difficult to restore confidence in Lebanon’s currency and its financial sector. Below we summarize the scenario and winners and losers amongst key stakeholders.

Source: IMF, World Bank, Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis. * Required bank capital refers to recapitalization needs for banks to meet a target of 8% RWA. Note: Liability management on LBP denominated debt does not involve Treasury bills/bonds held by the National Social Security Fund.

Another key challenge is to tackle the large $33bn negative net foreign currency position of BDL. There are different ways of tackling BDL’s negative FX position, with different implications for the economy (inflation, pressure on currency, bank recapitalization …) and the distribution of the losses among various stakeholders.

- One option is to force convert $33 bn of banks’ USD deposits at BDL (i.e. around 40% of banks’ deposits in case of 70% haircut on debt) from USD to LBP at LBP1,508. This will have negative implications on the exchange rate and inflation. Rebuilding BDL’s Net Foreign Assets from a deeply negative position to zero will translate into a massive increase in the money supply due to the proposed forced conversion at BDL level[8]. We estimate that the increase in the LBP monetary base under this scenario will be around 75%. The banks’ losses from the exposure to BDL could reach around $14 bn ($33 bn x the devaluation of the LBP – i.e. 42% if we assume the LBP at 2,600). The cost of bank recapitalization (adding the debt and NPL impact) would thus vary from $27 to $31bn (at 60 or 70% haircut), necessary to cover 8% of RWA.

- Another option would be to apply a 40% haircut on banks’ USD deposits and/or CDs at BDL equivalent to $33 bn. While thisoptioncould rebalance BDL’s FX position, it would increase the losses for banks compared to the forced conversion discussed above, implying higher recapitalization needs (estimated at $45-$49bn under scenario 4) and a larger impact on depositors. This is the case given that forced conversion will allow for preserving a residual value of the banks’ assets in LBP.

- A third, but sub-optimal option, would be for the government to issue $33 bn of new debt at lower interest rates (e.g. 2%). This ideally should be done in tandem with the restructuring of the Eurobonds but could bring the government’s foreign currency denominated debt to $42 bn (around 100%-110% of GDP under a 70% haircut scenario to the Eurobonds). The losses from the exposure to BDL for the Lebanese banking sector could reach $11 bn. While this option reduces (but does not eliminate) the pain on depositors, it does not tackle the core problem, namely Lebanon Inc’s net foreign currency position (which we estimate would remain at negative $30 bn or 75% of GDP). Moreover, public debt would remain high (peaking at more than 150% of GDP). Most importantly, the mix of debt will be heavily skewed towards foreign currency denominated debt which makes it more difficult for the government to reduce its debt burden over time. Simply put, trying to tackle a structural solvency problem by issuing more debt does not help.

For scenario 4 and the rest of this section, we consider the first option of forced conversion as the base case for tackling BDL’s negative FX position (Figure 60). We also assume that BDL’s negative FX position is fully adjusted, something which could be debated if we assume that a partial/gradual adjustment can take place if the BDL manages to generate positive P&L results. Moreover, we recognize that one could assign a certain (conservative) value to expected future privatisation proceeds and reduce the BDL’s FX adjustment commensurately. In that case, the remaining negative FX position of the BDL should not hinder confidence. This will ensure that privatisation is done adequately, and fire sales are avoided.

Source: IMF, World Bank, Lebanon’s Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis.

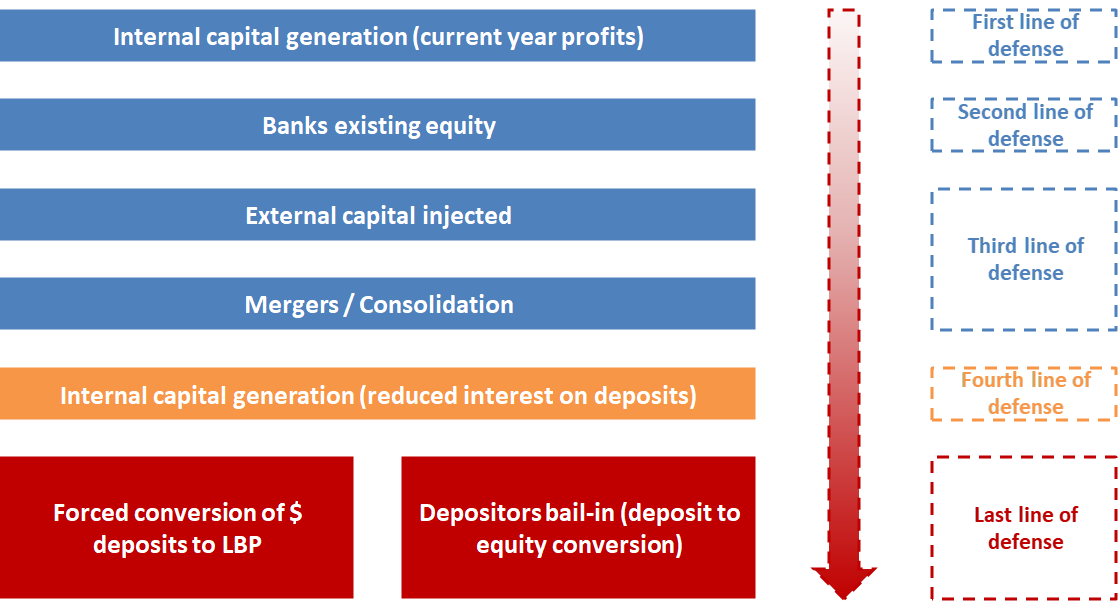

D- Recapitalizing banks while protecting small depositors

Given the scale of the expected losses, debt restructuring should be accompanied by a strategy for banks’ recapitalization that helps protect small depositors. The implications of various debt restructuring scenarios presented above on the banks’ balance sheets are significant with the recapitalisation requirements varying between $8 and $31 bn under a partial forced conversion of banks’ USD deposits/CDs at BDL, or up to $49 bn under a partial haircut of banks’ USD deposits/CDs at BDL. The BDL and the Banking Control Commission should establish a thorough assessment of the impact of these scenarios and devise a strategy for restructuring the banking sector with the objective of rebuilding a normal-sized banking sector post debt restructuring and improving its governance given its importance in supporting Lebanon’s growth recovery. This exercise should be part of the government’s macroeconomic framework as it mulls various options for debt restructuring.

Capital increases would be more effective if done after accounting for the impact of debt and BDL liabilities restructuring on banks’ balance sheets. This is crucial, particularly that piecemeal ad-hoc measures for the past few months (e.g. capital increase, forced “lirafication” of interest, lowering interest on deposits, capital withdrawals at the official exchange rate as opposed to black market rate), resulted in depositors’ absorbing the shock so far as opposed to shareholders’ equity. We therefore stress the urgency to implement a comprehensive debt restructuring anchored within a robust macroeconomic and fiscal policy framework. Otherwise the size of the future required bail-in from depositors will only increase with time if no action is pursued, and potentially hurt a larger number of depositors in the lower brackets as discussed below.

Bank restructuring will become costlier as pressures on the exchange rate intensify. In our model, we have assumed that the exchange rate adjusts to 2,600 in 2020 and beyond but recognize that this may be a conservative estimate. The table 61 below summarizes the impact of the currency devaluation on Lebanon Inc’s net foreign currency position and on the recapitalization needs of the banking sector under alternative exchange rates. The higher the currency devaluation, the higher the recapitalization needs as the losses on the banks’ local currency assets will be higher in USD terms[9].

Source: IMF, World Bank, Lebanon’s Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis.

Banks restructuring: Funding sources

Securing the funding for recapitalizing the banks should follow “the waterfall of loss distribution” to avoid hurting small depositors (Figure 62 below). The latter is based on the following key principle: Banks’ equity should absorb the losses first, and depositors’ principal / savings should be the last to be impacted. Only when the losses are too big to be absorbed by the banking sector’s existing equity (estimated at ~$21 bn) and all sources of external capital have been exhausted (existing shareholders, strategic investors, sale of banks assets, ….), then depositors principal / savings can become a source of capital.

Source: IMF, World Bank, Lebanon’s Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis.

Given the large scale of the implied losses, all possible fundraising options should be explored in order to recapitalize a right-sized banking sector able to support growth and preserve depositors’ savings. Some possible sources of funding include:

- Internal revenue generation through lowering interests on $ deposits to 1.5-2.0% (from currently ~6.5%)[10]. This can effectively generate around $3.5 to $4.0 bn of internal capital over 2 years.

- Recovered asset fund: some proposal for establishing an asset recovery fund and using its proceeds to protect depositors’ money could also be envisaged.

- Set up a bad bank funded by external investors: This would require a law. A more elaborate explanation is provided in “Saving the Lebanese Financial sector: Issues and Recommendations”

- Large depositors’ bail-in (deposit to equity conversion by tranches of deposit size) could be envisaged in a voluntary or mandatory way (if there is not enough voluntary subscription). Its key advantage is that it provides ownership and optionality for long-term profits (equity upside). This has been implemented in the past in Lebanon in a voluntary way (Intra Bank) and during the banking crisis in Cyprus for example.

- Partial forced conversion of deposits should be the option of last resort. To offset the losses driven by the forced conversion of $33 bn USD deposits at BDL (as suggested under scenario 4), banks could force their depositors to partly convert their USD deposits to LBP at an exchange rate of LBP1,508. This would be equivalent to ~27% of total $ deposits. Assuming a ~72% LBP devaluation (LBP2,600 per $1), this translates into a ~11% haircut on USD deposits. While the advantage of this approach is that it provides immediate liquidity to depositors, it subjects them to an immediate haircut on their deposits. This solution allows banks to avoid a currency mismatch on their assets and liabilities, which is critical.

Deposits concentration could render a potential solution easier and politically more feasible. Available data published in Al-Akhbar Newspaper in June 2019 suggests there are 225k accounts between $100k and $1m and 25k accounts above $1m (Figure 63). Combined, these represent ~8% of accounts in the banking sector. As such, a government’s comprehensive plan for fiscal reform, debt restructuring and bank recapitalization which aims to distribute the losses in an equitable manner by targeting large depositors (e.g. > $100k[11]) is not impossible or far-fetched. In fact, doing so could benefit the banks’ recapitalization:

- It provides credibility for the government in its willingness and ability to protect small depositors;

- It is akin to a wealth tax;

- It targets those that benefited the most from high interest rates over the last few years;

- It limits social unrest following the proposed restructuring and bank recapitalization;

- It ensures that the banks’ proforma shareholder base is not fragmented.

Source: IMF, World Bank, Lebanon’s Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis.

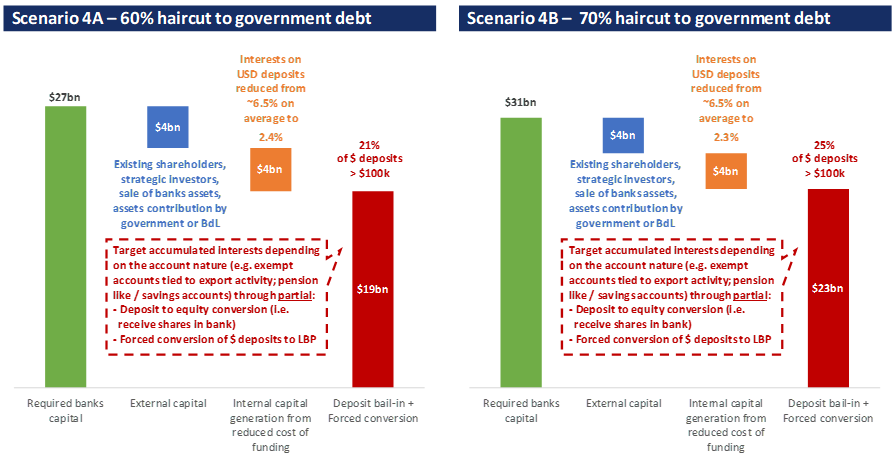

Banks’ recapitalization should be funded through existing shareholders, potential new ones, donor funding, and if needed through a depositor’s bail in program where the deposit to equity conversion is limited to 20-25% on USD deposits above $100k. As shown above, under scenarios 4A and 4B, the required funding to recapitalize the banks up to an 8% capital adequacy ratio is around $27 to $31bn if the haircut on the government debt reaches 60% to 70%. By applying the waterfall of losses, we estimate a $4bn external capital injection is required if we are to limit the deposit-to equity conversion for deposits above $100k to 20-25% under the bail-in program (Figure 64)[12]. The fresh capital injection could be achieved through various ways, including (i) raising capital from existing shareholders or strategic investors, (ii) the sale of banks assets (e.g. foreign assets, real estate), and (iii) revaluation of banks assets (e.g. real estate). In addition, we assume that $4 bn could be gained from lowering interest on USD deposits (from currently 6.5% to 2%). As a matter of fact, the more robust and credible the debt/BDL liabilities restructuring and bank recapitalization plans are, the higher the probability of attracting external financing to the sector and the less burden on depositors. In this regard, it is important to highlight that recommendations to dispose of public asset or create a fund to fund recapitalization of BDL and banks are not advisable given the weak governance environment in Lebanon. Such proposals in our view risk deepening state capture and would go against the principle of equitable burden sharing to which this paper adheres.

Finally, it would be possible to differentiate among targeted depositors to render the bail-in program more equitable and achieve other economic objectives. There is a possibility to go more granular in setting rules for bail-in deposits. Devising rules to consolidate the equity of the process and serving other economic policy objectives may be considered, including targeting accrued interest first (e.g. since 2015), and differentiating accounts based on the nature of their economic activity: (e.g. exempting offshore FX generating nature of account, large employers ….). Moreover, and in order to ensure a fair treatment of depositors, future banks’ profits could be restricted and assigned by order of priority as follows:

- Increase banks’ capital until it reaches a certain required capital ratio (e.g. 15%);

- Repay the principal loss due to the forced conversion of USD deposits to LBP;

- Compensate depositors that participated in the bail-in for any effective loss.

Having said that,a blanket rule and threshold for applying the deposit to equity conversion could be easier and more transparent to administer, reducing risks of abuse and corruption. As the debate about loss distribution and burden sharing matures further, it is extremely important to mitigate the risk and adopt a clear evidence-based communication strategy to explain the rationale, benefits and costs of a bail-in scheme.

Source: IMF, World Bank, Lebanon’s Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis. * Required bank capital refers to recapitalization needs for banks to meet a 8% RWA.

Delaying a comprehensive and well-designed debt restructuring and banks’ recapitalization plan is regressive. Absence of any policy framework and actions to deal with the insolvency of banks and the shortage of USD liquidity will continue to exact bigger losses on depositors, and notably smaller ones. Banks’ recapitalization under scenario 4 would require bailing in more than 40% of USD deposits above $100k if we wait for two years to implement the needed adjustment measures (Figure 65) even when $4 bn external capital injection is estimated to be made available to the banking sector as per above. As such, urgency is required as the cost of inaction is too high and increasing.

Source: IMF, World Bank, Lebanon’s Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis. * Required bank capital refers to recapitalization needs for banks to meet a target of 8% RWA. Note: Assumes LBP at 3,500 given continued monetization of the fiscal deficit through BDL, the erosion of FC reserves and implications of financial engineering operations on LBP.

Reducing the size of the bail-in through a partial forced conversion of banks’ deposits could bring Lebanon Inc’s net foreign currency position to positive territory. As discussed above, a deep debt restructuring and dealing with BDL’s balance sheet are critical to significantly reduce Lebanon Inc’s negative net foreign currency position. While scenario 4 will help reduce the large gap between USD assets and liabilities, only when opting for a partial forced conversion of deposits from USD to LBP (as opposed to a deposit-to-equity bail in) could Lebanon Inc’s net foreign currency position move into positive territory as shown in (Figure 66) below. This would be similar to what was done in other countries like Argentina. Policymakers should pay attention to this issue and accelerate the pace of reforms in order for Lebanon to be able to mobilize the required financing and avoid burdening smaller depositors and marginalized population with daily erosion of their savings.

Source: IMF, World Bank, Lebanon’s Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis.

The table below (Figure 67) summarizes the recapitalization needs of the banking sector under the different scenarios discussed above. We note that while scenario 4 implies the highest recapitalization needs for the banking sector amongst all scenarios, it is the least costly solution when considering BDL’s net negative foreign currency position.

Source: IMF, World Bank, Lebanon’s Ministry of Finance, Banque du Liban, authors’ analysis.

E- Launching a credible and socially responsible medium-term fiscal adjustment program

The proposed restructuring of the public debt and BDL’s liabilities, while recapitalizing the banking sector will need to be anchored within a medium-term macro-fiscal plan that supports social equity and growth. The absence of budgets between 2008 and 2017 severely weakened fiscal institutions, undermined the quality of fiscal policy formulation and sound public financial management. Since 2017, successive governments proved unable and/or unwilling to develop a new vision for economic growth away from the current unsustainable rentier model or rethink a new social contract that reduces excessive inequality in wealth distribution. The imperative for restructuring posed by the crisis is thus an opportunity to gear fiscal policy towards that direction.

Fiscal consolidation should be a cornerstone of the plan and target a realistic, politically feasible primary surplus. This paper does not delve into the details of the fiscal policy measures that should be included in any prospective plan. It is rather based on various analysis and studies that multiple stakeholders have been advocating for. We recognize however that front-loaded and aggressive fiscal austerity measures may not be politically feasible immediately. As such, in scenario 4, we targeted a primary surplus of 3.5% of GDP on average per year over the next 10 years (~1% on average in the first 5 years, and increasing afterwards), a difficult but not unrealistic objective if the set of policy measures is credible and consistent with the principles of equitable burden sharing and good governance.

- On the revenue side, the government should aim to gradually raise revenues to GDP from its 20.5% of GDP at end 2018 to 22% in 2025 and 24% in 2030, following a revenue collapse in 2020. The crisis offers the opportunity to reform Lebanon’s tax regime in a way that is more equitable and supportive of high-quality growth and productive private investment. New measures include penalties and taxes on investments in marine properties, higher taxes on property and reforms to the pension system in a way to increase coverage, and curbing tax evasion and corruption

- On the expenditure side, it would be extremely difficult to significantly cut primary spending. Lebanon’s primary expenditures averaged 21.2% over the past ten years, compared to 26.6% in Emerging Markets. As shown in Figure 8 above, the rigidity of the budget leaves limited room for manoeuvre in the short term, and requires an immediate focus on key elements:

- Lowering EDL deficit: We assume the government will undertake all necessary measures (raising tariffs, reduction of technical and non-technical losses, institutional reforms, switching to gas…) to reduce transfers from their current level of 3% of GDP to 0 by 2025-2027.

- Resizing the public sector based on functional review of ministries and state-owned enterprises: While this may prove difficult in the short run, possible measures could include hiring freezes, elimination of vacant positions, reduction of excesses in administrative and operational costs and a reform of state owns entities (SOEs).

- Reforming the social security benefit system in the public sector by accelerating pension reforms and increasing the contribution rate of public sector employees.

- Reducing the debt service payments through a deep restructuring of the public debt as discussed above. This should help bring down the interest payment to GDP to around 5% of GDP, down from 10-11% at present.

- Expanding social safety nets towards ~1.5% of GDP per year over next 5 years.

- Increasing the capital expenditures and directing it towards supporting a new economic growth model (smart infrastructure, environment related…), while improving its efficiency through public procurement and public investment management reforms.

In our model, we have assumed that savings resulting from EDL and other reforms are reallocated towards expanding and protecting social spending, while ensuring it is better targeted to support the most vulnerable and mitigate the impact of the crisis on the poor and the middle class.

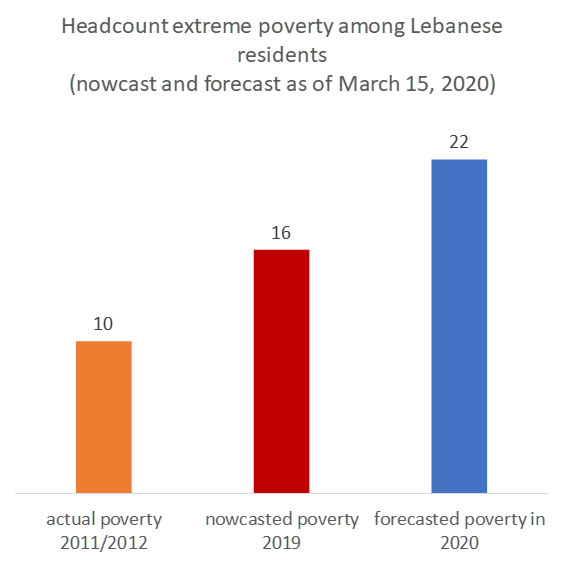

F- Mitigating the cost of the adjustment on the most vulnerable

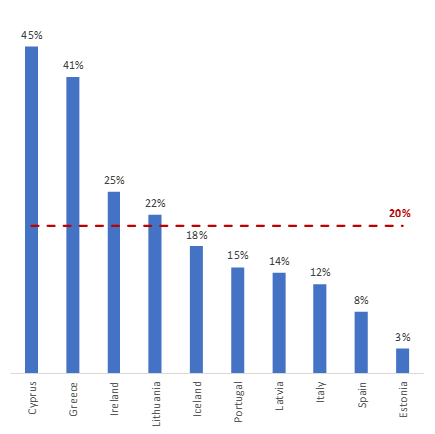

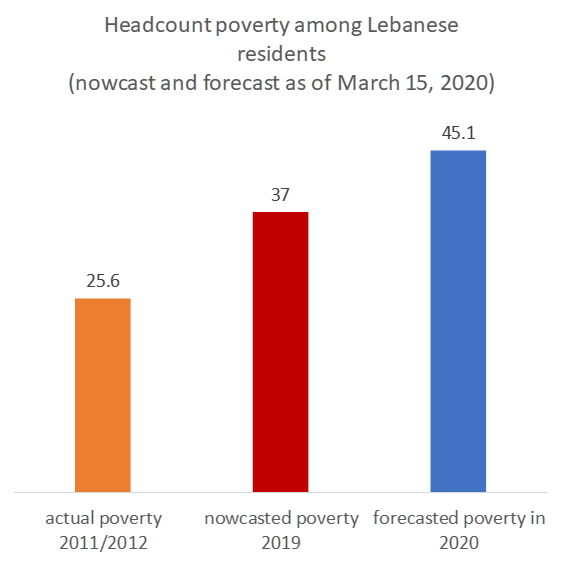

According to the World Bank, estimates indicate that around 37% of the Lebanese resident population lived in poverty in 2019, up from 25.6 percent in 2011-2012. In a recent statement, its Lebanon Country Director said that “what’s coming can be worse if not addressed immediately”, highlighting that “poverty could rise to 50% if the economic situation worsens; and that unemployment, especially among youth, is already high and could further rise sharply”. Indeed, international experience suggests that the major threats to the more vulnerable segments of society (notably the poor and the middle class) during a financial crisis are caused by a sharp contraction in economic activity and rising unemployment. Figures 68 and 69 portrays the extent of deterioration expected in 2020: almost 45% of Lebanese will fall below the poverty line (Figure 68) while 22% will below the extreme poverty line (Figure 69).

Source: World Bank staff calculations using Household Budget Survey 2011/12, and macro inputs from March 15, 2020.

It is therefore imperative to protect the most vulnerable and mitigate the large expected negative effects of the required adjustments. Social protection schemes in Lebanon are very thin and are being eroded by the impact of a depreciating LBP and rising inflation. According to the World Bank, only 10% of the population over age 60 receives any type of pension, leaving the most elderly reliant on family support, remittances or other types of informal care. Lebanon should therefore avoid mistakes done elsewhere and ensure that fiscal austerity does not come at the expense of the necessary spending on properly targeted social safety nets. We have thus made sure, in our model forecasts shown above, that the government ringfences social protection spending to the tune of 1.5% of GDP per year in order to better manage political backlash and social tensions, enhance equity through redistributive policies while building legitimacy and credibility.

Mitigation measures should in our view be all encompassing with support from the international community. This paper cannot delve into the details of the social mitigation measures, but believes the government should work closely with donors, and notably the World Bank in order to implement and ensure funding for key social programs such as:

- Expand the existing National Poverty Targeting Program and its related food voucher program;

- Protect spending on education and health while improving efficiency, including education grants/cash transfers to reduce dropouts and expand pro-poor universal health coverage;

- Accelerate pension reforms to ensure fiscal and social sustainability of National Social Security Fund;

- Devise a youth employment grant scheme if funding permits.

G- Establishing a credible exchange rate and monetary policy

Managing the exchange rate in a way to facilitate the adjustment of external (trade/current account) imbalances should be a core element of the macro-fiscal framework.The timing/sequencing and magnitude of the exchange rate adjustment will depend on the credibility of accompanying macroeconomic and fiscal policies and the availability of external funding. Given Lebanon’s large negative Net Foreign Asset (NFA) position and the resulting LBP overvaluation, an exchange rate adjustment is inevitable, especially that Lebanon’s current account deficit will likely remain large around 10% of GDP in the short to medium-term. The objective is to make it happen in an orderly fashion by ensuring that the fiscal, debt restructuring and bank recapitalization plan is conducive to closing BDL’s net negative foreign currency position, and supports the gradual build-up of net reserves with the help of external donor funding, ideally in the context of a comprehensive program with IMF oversight. The BDL should also devise a credible monetary policy framework and deploy its various liquidity and exchange rate management tools. Without these measures, the risk of the exchange rate overshooting and causing a spiralling hyperinflation becomes very high.

In parallel, proactive trade policy measures should support the external adjustment effort. The government should take proactive measures to reduce Lebanon’s import bill by opening a dialogue with the private sector on the one hand, and its trading partners on the other. Most trade agreements signed by Lebanon, and notably those with its main trading partners (EU countries), have clauses that could be used in the case of a BoP crisis. The Ministry of Economy and Trade should mobilize its trade negotiations teams towards that goal in addition to ongoing efforts aimed at boosting exports in cooperation with the ministries of Industry and Agriculture.

H- Boosting private sector growth

The sustainability of any crisis response will depend on its ability to reverse Lebanon’s economic growth contraction and putting people back to work. Accordingly, policy measures and initiatives to boost growth should constitute a key element of the policy framework which this paper will not delve into. Having said that, such initiatives should be geared to achieve two objectives:

- Growth enhancing structural reforms, including legal and regulatory measures aimed at improving the business environment, improving competitiveness, upgrading the bankruptcy and insolvency law and framework…etc.

- Investment growth stimulus aimed at upgrading and expanding the economic and social infrastructure to support private sector activity. Ideally, this should be part of a rethinking of the CEDRE framework, and the review of the priorities proposed in the Capital Investment Plan following the implementation of key structural reforms, and notably the establishment of regulatory authorities in key sectors, the enactment of a new procurement law and the implementation of the Public Investment Management Assessment recommendations.

| Pillar 1 | Pillar 2 | Pillar 3 | Pillar 4 | Pillar 5 | Pillar 6 |

| Macro-Fiscal adjustment and debt restructuring | Banking sector recapitalization and restructuring | Exchange rate and monetary management | Social protection and development policies | Growth stabilization and transformation (Private sector) | Governance and institutional reforms |

| Donor Engagement and external financing mobilization | |||||

| Communication and Stakeholders engagement | |||||

IV- Conclusion

This paper has shown that the scale and complexity of the Lebanese multi-dimensional crisis is extremely acute and requires immediate action given the exorbitant actual and future cost of reform delays and ad-hoc piece-meal policy decisions. Measures to stop the bleeding of FX reserves should take precedence first, including the establishment of a solid legal and regulatory basis for non-discretionary and transparent capital controls; and a strategic management of BDL’s remaining FX reserves.

In parallel, a solid, well-structured and coordinated policy and institutional framework to develop and implement a credible debt restructuring and growth recovery plan is a must. The only path to sustainable debt is laid out in Scenario 4, requiring a deep reduction in debt (60-70% haircut) and encompassing the foreign currency liabilities of the BDL. Such a restructuring should be accompanied by a robust framework for bank insolvency and plan for banking sector recapitalization to the tune of $25-30bn. We believe this is doable in a way that allows for an equitable burden sharing of the losses through a bail in program targeting large depositors (>100k), while protecting small depositors.

Importantly, the plan should be anchored within a robust and credible medium-term fiscal and growth recovery framework which aims at improving the composition of spending, raising revenues while improving wealth distribution, and rebuilding the stock of BDL’s net reserves in line with the standards of reserve adequacy. The plan should be also underpinned by strong commitment to public sector and public financial management and procurement reforms. The political viability of a fiscal consolidation plan would be dented if not accompanied by an acceleration of structural reform measures aimed at raising productivity, improving competitiveness, and tackling corruption.